![]()

| Key words | Tuberculosis, drug resistance, Isoniazid, Rifampicin, relapse |

Before the discovery of specific antibiotics for the

treatment of tuberculosis, there was no cure. Mortality of those with pulmonary disease

(disease of the lungs) was about 50%. The introduction of anti-tuberculosis drugs in the

1950s and the development of the various drug regimens meant that by the 1980s there was a

98% chance of cure. However, treatment had to be continued with good quality drugs for as

long six months to ensure cure. The difficulties in ensuring this occurs, especially in

resource poor countries, has resulted in an increasing incidence of tubercle bacteria

resistant to the most effective drugs; so called multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

In the second half of the 19th century, a

new movement for the treatment of tuberculosis came into existence; the sanatoria. These

were something of a cross between a hotel and a hospital where tuberculosis patients would

come and spend many months or even years. Treatment was a combination of sunlight, diet

and gentle exercise. It is doubtful whether the sanatoria improved survival of the

patients but may have reduced tuberculosis in the community by removing infectious

patients, so reducing transmission.

By the end of the 1930s surgeons were providing some means of treatment for tuberculosis

by various surgical procedures attempting to obliterate the cavities which formed in the

lung of seriously ill tuberculosis patients by collapsing part of the lung itself. These

techniques varied from introducing air into the pleural cavity (the artificial

pneumothorax,) to removing some of the upper ribs (thoracoplasty). Surgery usually took

place in the sanatoria, which then became more like a hospital and less like a hotel. The

surgical methods of treatment remained in vogue for the next thirty years until it was

realised that drug treatment alone provided effective cure.

By the end of the 1950s the introduction of drug therapy for tuberculosis was considerably

reducing the need for sanatoria beds in most developed countries. It was also realised

that drug treatment, which could be given at home, might be able to eliminate the need for

hospitalisation for all but the sickest tuberculosis patients.

|

A study directed by Wallace Fox of the BMRC and carried out by the Tuberculosis Research Centre in Madras, India, showed that home treatment of tuberculosis was just as successful as hospital treatment (Fig 1). This meant that the great expense of hospitalisation could largely be avoided, a very important saving in resource poor countries. |

| The author outside the Tuberculosis Research Centre with the director. Madras 1995. |

The development of drugs used for the treatment of tuberculosis.

Streptomycin, discovered in the USA during 1944 and

brought in to clinical use soon after, was the first specific anti-tuberculosis drug. The

apparent cure it provided, especially for children dying from tuberculous meningitis,

seemed little short of miraculous. But the joy was short lived as many children relapsed

after a few months of treatment, because the bacteria had developed resistance to

streptomycin. Fortunately other scientists in Europe were also working on a cure for

tuberculosis and developed para-aminosalycilic acid (PAS), which was brought into use in

the late 1940s. By combining the two drugs, streptomycin and PAS in the regimen the

emergence of drug resistant bacteria was largely prevented and cure became the norm.

By a sequence of elegant trials the British Medical Research Council (BMRC), at that time

under the directorship of Philip D'Arcy Hart, showed that the optimum length of treatment

for pulmonary tuberculosis using streptomycin and PAS was two years, though 18 months

provided almost the same cure rates. But streptomycin had to be given by intra-muscular

injection, which was painful for the patient and PAS had to be given in large quantities

by elixir and was nauseating.

Isoniazid, which remains the most effective drug at killing actively dividing tubercle

bacilli, was discovered and brought into clinical use in 1952. By combining all three

drugs, treatment length could be reduced to 18 months. Over the next two decades further

anti-tuberculosis drugs were discovered which could be added to the treatment regimen.

Some such as pyrazinamide, caused unacceptable side effects in the dosage used and fell

out of favour for a time. Others such as ethambutol, though not particularly effective in

killing bacteria, were useful in combination with other drugs in preventing the emergence

of resistance. Yet others such as ethionamide, and cycloserine, had both poor bacterial

killing ability and troublesome side effects, but were useful as reserve drugs for

patients who had developed resistant bacteria to the better drugs.

In the late 1960s a new and perhaps the most important drug in the treatment of

tuberculosis was discovered: Rifampicin. This drug was able to kill the very slowly

dividing bacteria, the so-called "persisters" in a way that the other drugs

could not. It was found that by combing this drug with at least two others initially, the

length of treatment could be reduced to as little as six months. So the new standard of

treatment of tuberculosis became isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R),and pyrazinamide (Z) for

two months followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for four months. This is conveniently

abbreviated to 2HRZ/4HR,

There never were enough places in sanatoria to cope with the number of patients who needed them. From the beginning of this century special nurses were therefore employed to visit tuberculosis patients in their homes; the tuberculosis health visitors. Their role was to give advice on how the disease might be contained in the home setting, reducing transmission to the family and providing support to the patient. When patients began to be treated at home, from the 1960s, the tuberculosis health visitors assumed a much more important role, ensuring that the patient completed their treatment and attended clinic as necessary. In Fox's Madras study the home visitor was especially important to ensuring patient compliance. Other centres, which also took part in BMRC studies, such as Hong Kong, actually required the patient to be seen to swallow their medication, so called directly observed therapy (DOT). The patient would call into the clinic, for example, on the way to work, and swallow their medication in the presence of medical staff.

Unfortunately the very success of the drug treatment of tuberculosis has been the catalyst for the emergence of a new wave of drug resistance. Patients have been allowed to take their medication at home completely unsupervised. The experience of the early single use of streptomycin taught us that taking one drug on its own for tuberculosis would lead to drug resistance. There is a danger that if the patient is sent home with three separate drugs, he or she might take a single drug at a time. In the patient with extensive lung disease taking a single drug for just a few days may allow drug resistance to emerge. If a patient happens to be resistant to one drug and takes a combination of two drugs including the one to which he is resistant, drug resistance to the second drug will emerge. Similarly if the patient is resistant to two drugs, and takes these two drugs and a third only, then resistance to the third will emerge and so on. In this way a combination of poor compliance and poor medical supervision may result in multi-drug resistance.

Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is defined as

resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin whether there is resistance to other drugs or not.

It is therefore incorrect, by this definition, to classify a patient has having multi-drug

resistant disease if they have an infection with a bacterium susceptible to rifampicin but

resistant to many other drugs.

In practice resistance to isoniazid and streptomycin only is probably the commonest form

of resistance world wide to more than one drug. This is not strictly multi-drug

resistance. Perhaps another separate term is needed to define this combination of

resistances. Resistance to streptomycin, isoniazid and another drug or drugs, not

including rifampicin, is probably very uncommon indeed.

| Table of drugs used for the treatment of tuberculosis. | ||||

| First line drugs | Second line drugs | |||

| Essential | Other | Old | New | |

| Isoniazid Rifampicin |

Pyrazinamide Ethambutol Streptomycin |

Ethionamide Cycloserine Capreomycin Amikacyn Kanamycin PAS Thiocetazone |

Quinolones | |

| ofloxacin ciprofloxacin sparfloxacin |

||||

| Macrolides | ||||

| clarithromycin | ||||

| Clofazimine Amoxycillin & Clavulanic acid |

||||

| New rifamycins Rifabutin Rifapentine |

||||

The table above shows the drugs available for the

treatment of tuberculosis. The two on the left, isoniazid and rifampicin, are by far the

most important; isoniazid because it kills the great bulk of bacteria, rapidly rendering

the patient non-infectious within days of starting treatment and rifampicin because it

eliminates the persisting bacteria (so called sterilisation) allowing treatment time to be

shortened considerably. Treatment with these two drugs alone for nine months will provide

cure in 95% of cases. However patients should not be started on two drugs alone in case

resistance is present to one of them. In practice the new patients should be

started on isoniazid and rifampicin plus at least one drug from the second column. The

addition of pyrazinamide for the first two months only allows treatment to be given for as

little as six months (see above). If ethambutol only is given for the first two months of

treatment instead of pyrazinamide, the total time of treatment should be nine months.

Because of the emergence of more drug resistant cases world-wide, the current

recommendation is to give two drugs from the second column; pyrazinamide and ethambutol,

in addition to isoniazid and rifampicin until culture and sensitivity results are

available.

In patients who have had previous treatment i.e.; are not "new" a more complex

regimen may be needed initially. It is important that the four drug regimen is continued

until culture and sensitivity results are available as these may take longer than two

months. (see below)

I was recently asked to see a patient from a city

far away who had developed multi-drug resistant tuberculosis as a result of an unfortunate

series of events, principally due to poor medical supervision. He is a 65-year-old

Pakistani man who came to the UK about thirty years ago. A year before he was referred to

me he was admitted to his local district general hospital with a pneumnoia. A chest x-ray

showed a cavitating shadow in the upper lobe of his left lung and sputum samples were

positive on smear and (later) culture for M.tuberculosis. A diagnosis of

tuberculosis was made and he was started on isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide. He

improved satisfactorily initially as an in-patient and then at home. After two months he

was seen in the clinic and the pyrazinamide was stopped before sensitivity results were

available. Three weeks later the sensitivity results were available showing him to

have bacteria resistant to isoniazid. He was recalled to clinic and ethambutol alone was

added. Over the next few months, although not particularly unwell he did not improve much

either. Sputum was again taken for smear and culture. These remained positive and when the

sensitivity results came back for the second time the patient's bacteria were found to be

resistant to isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and streptomycin. He was again seen in the

clinic when pyrazinamide alone was reintroduced.

The initial three drug starting regimen was correct for the guide lines current at the

time. In this situation it did not matter that four drugs were not given initially. The

medical services first mistake was to change the regimen before sensitivity results were

available. Had the doctor waited for the results, which showed resistance to isoniazid,

the patient could have been continued on rifampicin and pyrazinamide and cure would

probably have resulted after six to nine months of therapy.

The second mistake was to add a single drug to a regimen of isoniazid and rifampicin when

it was known that the patient had been resistant to isoniazid from the start and had

effectively been on a single agent; rifampicin, for three weeks. At this stage at least

three drugs should have been added, not one. The result of adding only one was that the

bacteria became resistant to that one too. It was at this point that the doctor made the

third mistake, again adding in a single drug, pyrazinamide, to a regimen, which was

failing. The result at the end of a year is that instead of a cured patient with former

resistance to the relatively treatable combination of streptomycin and isoniazid, we have

a patient with continuing disease, now resistant to streptomycin, isoniazid, rifampicin,

ethambutol and probably pyrazinamide. All first line drugs are likely to be useless.

The treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

is specialised, complex and expensive and should only be undertaken at recognised centres

with experience of managing such patients. Fortunately the numbers of these patients in

the UK are still relatively low. For the clinician faced with a patient with tuberculosis

there is no sure way of knowing that the patient has a drug resistant bacteria until

culture results are available and these may take some weeks.

The clinician must therefore be aware of risk factors which may raise the possibility of

drug resistant tuberculosis and put the doctor on his guard. The following are important

risk factors for drug resistance.

If drug resistance is suspected a detailed history

of possible tuberculosis drugs which the patient has had before must be obtained. The

patient should then be put on at least three drugs and preferably four to which they have

not had previous exposure. Isoniazid and rifampicin should also be given at the start as

if the strain, which the patient is infected with, is sensitive to these drugs time will

be gained by giving them from the start. In the immigrant streptomycin resistance is so

common that this should not be included in the regimen even if the patient has not been

exposed to it previously.

For example, if the patient has had previous treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin,

ethambutol and pyrazinamide, isoniazid and rifampicin should be given, an injectable drug

such as amikacin, at least one of the old drugs such as ethionamide and one of the new

drugs such as ciprofloxacin. Cycloserine could be used as a fourth drug if required. Thus

the potentially drug resistant patient will be started on six drugs. The danger of adding

a single drug to a regimen already being given will therefore be avoided.

Never add a single drug to a failing regimen.

When drug resistance is known the regimen can be

tailored accordingly.

The new rifamycins can be used in place of rifampicin but bacteria resistant to rifampicin

are also likely to be resistant to these compounds. Rifapentine, which can be given once

weekly, may prove to be effective in preventing the emergence of drug resistance.

Drug therapy for resistant tuberculosis carries a

success rate considerably lower than for sensitive disease; 60%-70% cure compared with

over 95%. Surgery is sometimes a useful adjunct. If disease is confined to one or at the

most two lobes, lobectomy offers a better chance of cure than continued drug treatment.

Fig 2.a) & b) show a patient with multi-resistant disease who found the second line

regimen of drugs intolerable. He underwent left upper lobectomy with good results (Fig.2

c)).

|

|

| Figure 2a Chest x-ray of patient with MDRTB showing a cavity in the left upper lobe |

Figure 2b Section of a CT scan showing an isolated thick walled cavity. |

Figure 2c A chest x-ray of the same patient after left upper lobectomy |

HIV positivity does not of itself increase the chance of drug resistance. But HIV does considerably accelerate infection developing into disease. In settings or communities where there is a high prevalence of HIV the introduction of tuberculosis will cause a rapidly developing "epidemic." If drug resistant tuberculosis is introduced then the "epidemic" will be drug resistant. This has been clearly shown in a number of mini-epidemics. Those in the USA during the 80s showed patients to have an average mortality of only a few weeks with HIV positive drug resistant tuberculosis. Improved treatment for HIV infection with anti-virals has considerably improved prognosis recently. Two notable hospital based mini-epidemics have also occurred in London within the last five years. It is now appreciated that drug resistant tuberculosis in the presence of HIV, requires especially stringent methods to control cross-infection such as confinement of the patient to a negative pressure room, and especial precautions for nursing.

Against this depressing background of disease and drug resistant increase there has been some encouraging evidence of new resources being invested in the battle against tuberculosis. Of most importance is the full sequencing of the M.tuberculosis genome. We now know the genetic structure of the bacterium and, in time, this should enable us to develop new drugs and vaccines against it. In the meantime some other developments in molecular biology are already proving useful.

Traditional methods of confirming the diagnosis of tuberculosis by smear and culture are insensitive and slow. Only approximately one half of pulmonary tuberculosis is sputum smear positive and bacteria can take weeks to grow on culture medium. Even the use of liquid media can take many days to confirm the diagnosis. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR),is a method of DNA augmentation, which can rapidly multiply the bacterial DNA potentially giving a "culture" result within hours of taking a specimen from the patient. The essentials of the PCR reaction are shown in Fig 4.

Figure 4

Diagram showing a simplified account of the chemical steps involved in the polymerase

chain reaction. Two DNA strands are created from one after a single cycle.

A particular sequence of DNA specific to M.tuberculosis is first extracted using

restriction enzymes. The target DNA is then denatured into two separate strands by

heating. The binding of specific primers can then take place. Series of base pairs can be

added from the tips of the primers to eventually build up the whole template. Thus two

strands of DNA are made from one. If this process is repeated 30 times approximately

1,000,000 strands of DNA will result. Use of gel electrophoresis and a gene probe can then

identify the particular DNA sequence chosen on the genome specific for M.tuberculosis.

Commercial kits (such as the Accuprobe system from Gen-Probe) can identify a culture as

being from M.tuberculosis or M.avium within 2 hours.

In practice there have been a number of teething problems with the technique.

Contamination can result in false positivity. Sensitivity is not as good as traditional

solid media based culture and the method is comparatively expensive.

The Federal Drug administration of the USA has licensed the technique only for identifying

the organism in the AFB sputum smear positive patient. Its use for non-respiratory

tuberculosis particularly for the examination of CSF in tuberculosis meningitis has not

been thoroughly worked out.

It is hoped that new generations of kits will improve sensitivity.

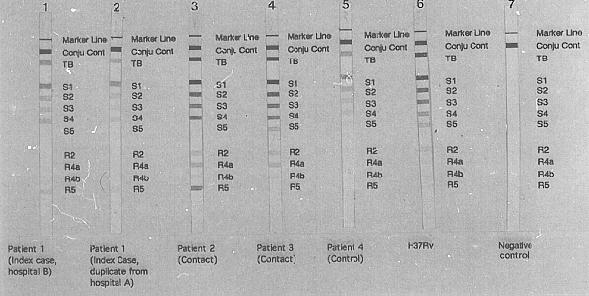

A variety of PCR-based methods with the potential to offer rapid drug sensitivity testing has been evaluated. The technique of single-stranded conformation polymorphism (SSCP)has been used to identify a number of different drug resistant phenotypes in selected organisms. In M.tuberculosis infection the important drug sensitivity is to Rifampicin. The Inno-LiPA Rif.TB kit (Inno-genetics, Belgium), a line hybridisation assay, specifically detects rifampicin resistance after amplification of the relevant region of the beta subunit of the RNA polymerase (rpoB) gene of M.tuberculosis. From the pattern of hybridisation on the Inno-LiPa test strips, rifampicin resistance or sensitivity can be easily established. Fig 5. shows a typical test result obtained in a case of rifampicin resistant tuberculosis. In this case a mutation in the region of the wild type probe S4 with a lack of hybridisation of this probe and binding of the mutant probe R4a has occurred. This kit permits rapid identification of rifampicin resistance within 96 hours of receiving a sample.

Figure 5

Gel electrophoresis demonstrating the rifampicin resistance gene. Note the presence of a

band at position R5 in the four left-hand specimens which is not present in the control

patient, (third from right.) This indicates a mutation to rifampicin resistance in the

infecting organism of these patients.

|

As with most things in medicine,

prevention is better than cure. In order to ensure that the patient is taking medication

correctly WHO now strongly advocate the use of directly observed therapy (DOT). This simple procedure means that the patient must be seen to swallow their medication under the eye of a trained (not necessarily medically ) supervisor. This prevents drug resistance emerging as it should ensure that monotherapy is avoided. |

Drug resistant tuberculosis is increasing. Its

treatment is costly and lengthy. New rapid methods of detecting drug resistance are

helpful but too costly to be used in developing countries. Development of new drugs is

also very costly and not seen as a priority in the market orientated economics of the

pharmaceutical industry. Prevention of drug resistance by directly observing the patient's

therapy must be the first priority of any tuberculosis service. Drug resistant

tuberculosis poses an enormous threat to world health and its medical resources.

| Books | The White Death. A history of tuberculosis, Thomas Dormandy. Hambildon Press. London 1999. Clinical

tuberculosis, Clinical tuberculosis 2nd Edition.

|

|---|---|

| Manuals | Guidelines for the management of drug resistant

tuberculosis John Crofton, Pierre Chaulet, Dermot Maher. WHO Geneva 1997. TB/HIV A clinical manual TB A crossroads |

| Papers | Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British

Thoracic Society. Chemotherapy and management of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom:

recommendations 1998. Thorax 1998;53:536-548. An outbreak of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in a London teaching hospital. Breathrach AS, de Reiter A et al. J. Hosp Infect. 1998;2239:111-117. Pablos-Mendez A, Raviglione MC, Laszlo A et al for

the World Health Organisation-International Union Agaonst Tuberculosis and Lung Disease

Working Group on Anti-tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance. Global surveillance for

antituberculosis drug resistance, 1994-1997. Database study of antibiotic resistant

tuberculosis in the United Kingdom, 1994-6. |

All Pages copyright © Priory Lodge Education Ltd

1999