Browse through our Medical Journals...

A survey of current practice in the management of insomnia

Andrew Donaldson, Nabila Muzaffar

Abstract

Aims and method

This study examines current practice in the management of insomnia in a sample of GPs and psychiatrists. We compare current practice with NICE guidance and look at ways of improving management.

Results

Current management seems to vary widely and differs between GPs and psychiatrists. NICE guidance does not appear to be widely followed.

Clinical Implications

There is a need for guidelines on the management of insomnia to improve current practice. A proposed flowchart is presented incorporating NICE guidance.

Introduction

Insomnia is one of the commonest problems patients present with to health care practitioners. Studies estimate the prevalence of insomnia to be between 10 and 38% depending on the criteria used3. Sleep disturbance can lead to physical and mental health problems as well as social, occupational and economic repercussions1, 2.

Medication is frequently used in the management of insomnia. Until recently, there has been little guidance on the use of pharmacotherapy and prescribing practices have been varied. In April 2004, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) published guidance on the use of zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone for the short term management of insomnia.

This study was conducted four months after the NICE guidance was published and was designed to evaluate current practice in the management of insomnia in a sample of general practitioners and psychiatrists.

Method

A questionnaire was devised and posted to all specialist registrars and consultants in psychiatry in Forth Valley NHS (28 doctors). A random sample of 30 general practitioners in the area were also sent questionnaires. All replies were identified as being from hospital or general practice doctors but were otherwise anonymous.

The questionnaire looked at the following issues: which hypnotic is most frequently used, the usual maximum length of hypnotic prescription, management after failure of first line medication, use of anti-depressants and anti-psychotics in insomnia, use of non-pharmacological methods, awareness of NICE guidance.

Results

24 consultants and specialist registrars in psychiatry returned questionnaires (86% response rate). 24 general practitioners returned questionnaires (80% response rate).

Zopiclone was the most frequently prescribed hypnotic in this study. 24 respondents (62%) would normally prescribe zopiclone as their first line hypnotic (15 psychiatrists, 9 GPs). Temazepam is the first choice hypnotic with 13 (33%) of the respondents (5 psychiatrists, 8 GPs). One psychiatrist (3%) and one GP (3%) used zolpidem as first line treatment. No respondents used other medications as first line hypnotics. (9 questionnaires were excluded for having more or less than one answer).

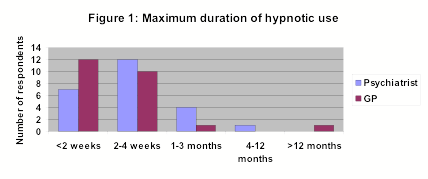

The longest duration respondents would consider prescribing a hypnotic for is shown in figure one.

|

31 respondents (65%) would prescribe a different class of hypnotic if the patient did not respond to the initial prescription (17 psychiatrists, 14 GPs). 17 (35%) respondents would not use another hypnotic.

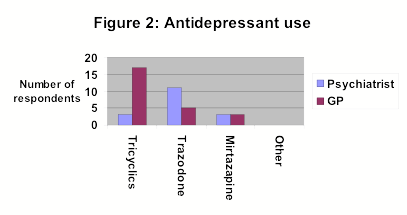

Figure two represents respondents who would consider prescribing anti-depressants in patients with insomnia but no evidence of depression.

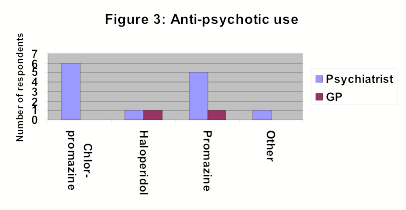

Figure three represents respondents who would consider prescribing anti-psychotics patients with insomnia but no evidence of psychosis.

46 respondents (96%) said they usually give verbal advice on sleep hygiene but only 9 (19%) gave written information (5 psychiatrists, 4 GPs).

Only 8 respondents (17%) regularly used other non-pharmacological methods to help with sleep (4 psychiatrists, 4 GPs).

47 respondents (98%) would consider referring to educational classes which provided information on the non-pharmacological management of insomnia.

27 (56%) respondents were aware of the recent NICE guidelines on hypnotic use (18 psychiatrists, 9 GPs).

Discussion

This study demonstrates the continuing wide variations in the management of insomnia. Prescribing habits seem to have been influenced little by the recent NICE guidelines.

Zopiclone and temazepam account for most of the hypnotics prescribed by doctors in this study. This is reflected in the annual drug budget for hypnotics in Forth Valley with 35% of the total budget spent on zopiclone and 30% on temazepam. The NICE guidance recommends that Òbecause of the lack of compelling evidence to distinguish between zaleplon, zolpidem, zopiclone and the shorter acting benzodiazepine hypnotics, the drug with the lowest purchase price should be prescribedÓ3. If this guidance is followed and British National Formulary (BNF) prices are applied, it would appear that temazepam is the most appropriate hypnotic for first line pharmacological use. Of the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, zolpidem appears to be the least expensive and therefore an appropriate second line hypnotic agent.

There is no evidence that changing to a different class of hypnotic, after failure to respond to first line treatment, is beneficial3. The majority of respondents to this questionnaire still consider this to be an appropriate response, however. NICE have advised that switching class of hypnotic should only be considered if a patient experiences adverse effects directly related to the first line treatment. If this guidance is followed, temazepam would be suitable for the vast majority of patients requiring pharmacotherapy and only a small minority would require a second line hypnotic. This should result in significant savings in pharmaceutical budgets.

Both the BNF and NICE guidance advise a maximum prescription length for hypnotics of three to four weeks. Most doctors in this study appear to be applying this to practice but some still prescribe for longer periods which may lead to dependence.

Neither anti-depressants nor anti-psychotics are licensed for use in insomnia. As can be seen from the study results, however, both these classes of drugs are frequently used. General practitioners appear more willing to try anti-depressants, most commonly tricyclics. Psychiatrists are more familiar with anti-psychotics and this is reflected in their prescribing pattern in insomnia. There is no convincing evidence for the use of any of these drugs in insomnia and their prescribing is not recommended.

Non-pharmacological methods for the management of insomnia have been given a high priority in the NICE guidance. This can be anything from simple advice on sleep hygiene to more structured programmes such as sleep restriction therapy. Although most respondents did give some verbal advice on sleep hygiene, few gave written information. This would seem to be a reasonably inexpensive way of helping to improve patients sleeping patterns. Local education classes on sleep hygiene and possibly other forms of non-pharmacological methods may be helpful. The cost of setting up such classes would hopefully be off-set at least partially by the reduced spending on medication. All but one of the respondents would consider using such a service if available.

Interestingly, over half of the respondents were aware of the recent publication by NICE on hypnotics yet practice still varied considerably. It is worth noting that NICE advice applies primarily to England and Wales but the situation in Scotland should be similar.

As current prescribing practice appears to be so varied it seems appropriate that guidelines for the management of insomnia should be available. Incorporating the NICE guidance, the following flowchart has been devised:

| Ensure a full history and examination is carried out |

| then |

| Exclude any treatable causes of insomnia eg depression, pain, urinary problems |

| then |

| Give verbal and written information on sleep hygiene |

| Consider referral to sleep education classes |

| If not successful consider short term hypnotic use |

| Suggested hypnotics: 10-20mg temazepam (firstline) or 7.5mg zolpidem ( both max 3-4 weeks) |

| Patients who do not respond to one hypnotic should not be switched, switching should only be for side effects (not contraindications of suggested drugs) |

We would recommend that local guidelines, similar to the above, be devised to help practitioners with the management of insomnia.

Declaration of interest: None

References

1. Bliwise, D.L. (1991) Treating insomnia: pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 23, 335-341

2. Morin, C.M., Culbert J.P., Schwartz, S.M. (1994) Nonpharmacological interventions for insomnia: a meta analysis of treatment efficacy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1172-1180

3. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Technology appraisal guidance 77 (2004) Zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone for the short term management of insomnia

First Published February 2005Click

on these links to visit our Journals:

Psychiatry

On-Line

Dentistry On-Line | Vet

On-Line | Chest Medicine

On-Line

GP

On-Line | Pharmacy

On-Line | Anaesthesia

On-Line | Medicine

On-Line

Family Medical

Practice On-Line

Home • Journals • Search • Rules for Authors • Submit a Paper • Sponsor us

All pages in this site copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-