Browse through our Medical Journals...

Human Growth Hormone in the treatment of Biological Depression

Dr Ben Green MRCPsych FHEA, Consultant Psychiatrist and Hon. Senior Lecturer.

Introduction

This paper is a single case report regarding the use of rDNA derived HGH in an adult patient with recurrent depression. Bearing in mind the severe limitations of such a paper this report makes the case for further evaluation of a novel potential biological treatment for depression.

Physiology of Human Growth Hormone

Beyond its role in human growth Human Growth Hormone (HGH) has been termed a master hormone governing the activities of various subsidiary hormones and various key aspects of metabolism. Childhood HGH deficiency results in pituitary dwarfism. Adult HGH deficiency is less obviously recognisable. HGH is largely responsible for repair mechanisms. The secretion peaks in the early hours of the morning before normal wakening.

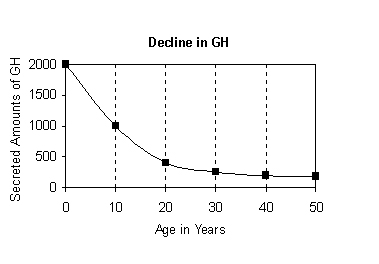

HGH secretion diminishes with age. The swiftest decline occurs in middle age. Curiously enough this is also the same age at which biological depression also starts to appear in humans.

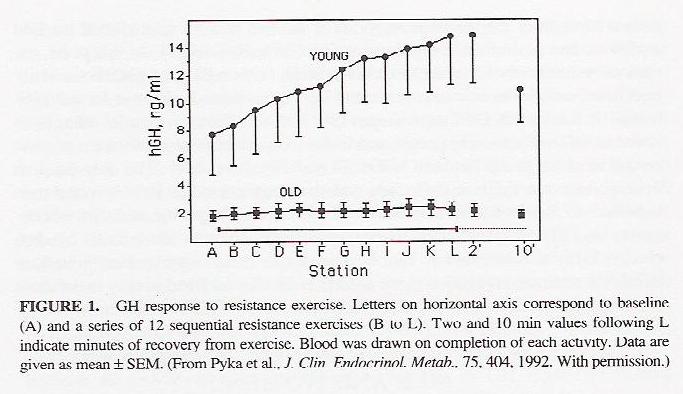

Similarly GH response to physiological stress is more blunted in the elderly:

80% of adults with GH deficiency (GHD) do not have a history of childhood-onset GHD; they acquire GHD in adult life, usually through acquired damage to the pituitary-hypothalamic region (Merriam et al, 2004). These may include people with pituitary problems or cancer survivors who have had radiotherapy (Mukherjee, 2005) or traumatic brain injury (Kelly et al, 2006).

Symptoms of Adult Growth Hormone Deficiency and Depression

McGauley (1989) first recognised the beneficial effects of GH replacement on Quality of Life in adult GHD patients. Replacement GH in adult GHD has maintained its effects of Quality of Life (QoL) when administered over a 9-year period (Gilchrist, Murray,& Shalet, 2002). Significant effects on QoL including depression were noted in patients on GH compared to individuals who had discontinued treatment. Further evidence that GH is responsible for these effects was seen in the study by McMillan et al (2003) where psychological benefits disappeared on discontinuation. Psychological deterioration was noted in terms of decreased energy, and increased tiredness, pain, irritability and depression. Effects of GH on QoL tend to diminish within 6 months of discontinuation (Stouthart et al, 2003), but begin again on restarting GH therapy.

Atypical depression has been described in adult onset growth hormone deficiency (GHD) by Mahajan et al (2004). The association seems specific to adult onset GHD as opposed to child onset GHD. In their study of 25 GHD patients 11/18 (61%) of the patients with adult onset GHD, but 0/7 of the patients with childhood onset GHD, had atypical depression at baseline. After two months of GH therapy there was an effect on depression with significant improvements found on depression rating scale scores after 2 months of GH therapy, with significant improvements in emotional reaction and social isolation scores from 1 month, and in energy levels and sleep disturbance from 2 and 3 months respectively.

The manufacturers of one HGH preparation describe the behavioural manifestations of ADHD and suggest the following questions to identify potential behaviours of adult GHD sufferers:

* Do they often feel tired and lack energy?

* Do they experience a decrease in ability to exercise?

* Are they unhappy with the way they look?

* Has their social interaction decreased?

* Do they feel isolated?

Symptoms of Adult Depression overlap with Adult Onset GHD

Tiredness, lack of energy, reduced interests and social isolation are recognised features of depression. Hence the intuitive leap towards using HGH in persistent or severe cases of depression.

Dosing Issues

Given the lack of any clinical trial or even patient series the use of GH in the treatment of depression can be considered wholly new therapeutic territory. Dosing in adult GHD has shifted to an individualized dose-titration approach, where treatment is started at a low dose and then titrated upward until IGF-I levels normalize, significant side effects develop, or beneficial effects plateau (Merriam et al, 2004). Women seem to require higher GH doses than men. The doses are given by injection and daily, although there has been some experimentation with alternate day dosing (Giavoli et al, 2003).

Adverse Effects of HGH

Adult-onset GHD patients report an increased incidence of arthralgia, myalgia and paraesthesia with significant increases in fasting glucose and hypertension in 7.7% after 18 months of hGH, which was within the expected prevalence range for the patients anyway (Chipman et al, 1997). However, there may be additional compensatory health benefits in the middle aged including a lowered cholesterol level (Leese et al, 1998). Some early fears about the risks of inducing diabetes have led to further research which suggest a less worrying tendency than at first imagined. (Brasil et al 2007). They concluded that 24 months of therapy with hGH did not seem to have affected glucose homeostasis in some 13 patients with GH treated GHD.

Extension of Indications for GH beyond GHD

Manufacturers of GH may well be reluctant to consider extending the indications for GH. There have been some small scale studies that are suggested indicate adverse effects such a tumour promotion. Despite these a large market in potentially ineffective GH treatments (oral GH, GH precursors) has sprung up to make profit out of claims that GH has an anti-ageing effect. This potential for abuse has been recognised for some time (Neely & Rosenfield, 1994).

Case report

A 43-year-old man, who had been suffering with recurrent depressive disorder since the age of 31, was again becoming depressed. He was on a regime of escitalopram 10 mg daily and was tired of using antidepressants. He had been on regimes of fluoxetine, paroxetine and escitalopram over the past twelve years.

He was started on a regime of injected HGH (1.8 IU HGH daily).

He noted an improvement in mood and a marked reduction in tiredness within four days of starting the regime. A side effect of a dry mouth was noted in the first week. Sleep disturbances (early morning wakening) ceased during the second week of treatment. There were improvements in concentration, energy, anhedonia and libido.

Escitalopram was discontinued by halving the tablets and then halving them further over the next two weeks.

His mood remained buoyant despite the cessation of the antidepressant. The patient noted a return to normal patterns of sleeping for the first time in many years.

At follow up six and twelve months later the patient was asymptomatic in terms of his depression. He had reduced his use of HGH to injections four times a week. He reported that he found the injection no more inconvenient than taking tablets and preferred the experience of being on the HGH more than any previous oral antidepressant.

Discussion

That the above approach to treating depression is entirely novel is conceded and in the absence of other case reports or case series what follows is largely speculative. The success of the treatment would sugegst a number of hypotheses for testing: firstly that the age-related decline in HGH secretion may be relaetd to the development of 'biological' adult depression. Secondly that rDNA HGH might be considered (via research) alongside other physical treatments for depression.

The ability to function normally socially and occupationally without recourse to antidepressants for the first time in a decade is noted. No relapse occurred off antidepressants suggesting a therapeutic effect for the HGH.

If HGH was considered to be a therapeutic treatment for biological depression then its use could be extended to refractory cases or cases requiring ECT.

The notion of self-dosing with injections of HGH may be unpalatable for many patients. that the patient in this report found the regime more tolerable to oral antidepressants may suggest an improved QoL over and above that yielded by conventional antidepressant therapy.

Limitations and the Need for Future Research

This is a single case report. There would need to be a case series and then an argument made for a therapeutic trial. This would be costly and funding and ethical approval would need to be sought. The novel nature of the treatment may be off putting to many institutions and I have previously commented on the potential reluctance of manufacturers to over-extend the indications for such a product.

A range of studies suggesting adverse mortality in historical small scale studies of seriously ill ICU patients and concerns about potential tumour promotion may reasonably underlie such fears.

The treatment phase considered in the case report is only 12 months - however I note that many drug trials may be for significantly shorter periods, indeed weeks.

I would particularly like to see evaluation of HGH as a treatment for refractory depression, patients with depression severe enough to warrant ECT and extended trials of HGH in recurrent adult depression.

References

Brasil, R Resende de Lima Oliveira. Soares, D Vieira. Spina, L Diniz Carneiro. Lobo, P Marise. da Silva, E Maria Carvalho. Mansur, V Aleta. Pinheiro, M F Miguens Castelar. Conceicao, F L. Vaisman, M. (2007) Association of insulin resistance and nocturnal fall of blood pressure in GH-deficient adults during GH replacement. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 30(4):306-12.

Chipman, J J. Attanasio, A F. Birkett, M A. Bates, P C. Webb, S. Lamberts, S W. (1997) The safety profile of GH replacement therapy in adults. Clinical Endocrinology. 46(4):473-81.

Giavoli, C. Cappiello, V. Porretti, S. Ronchi, C L. Orsi, E. Beck-Peccoz, P. Arosio, M. (2003) Growth hormone therapy in GH-deficient adults: continuous vs alternate-days treatment. Hormone & Metabolic Research. 35(9):557-61.

Gilchrist, F J. Murray, R D. Shalet, S M. (2002) The effect of long-term untreated growth hormone deficiency (GHD) and 9 years of GH replacement on the quality of life (QoL) of GH-deficient adults. Clinical Endocrinology. 57(3):363-70.

Kelly, Daniel F. McArthur, David L. Levin, Harvey. Swimmer, Shana. Dusick, Joshua R. Cohan, Pejman. Wang, Christina. Swerdloff, Ronald. (2006) Neurobehavioral and quality of life changes associated with growth hormone insufficiency after complicated mild, moderate, or severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 23(6):928-42.

Leese, G P. Wallymahmed, M. VanHeyningen, C. Tames, F. Wieringa, G. MacFarlane, I A. (1998) HDL-cholesterol reductions associated with adult growth hormone replacement. Clinical Endocrinology. 49(5):673-7.

Mahajan, Tripti. Crown, Anna. Checkley, Stuart. Farmer, Anne. Lightman, Stafford. (2004). Atypical depression in growth hormone deficient adults, and the beneficial effects of growth hormone treatment on depression and quality of life. European Journal of Endocrinology. 151(3):325-32, 2004.

Merriam, George R. Carney, Colleen. Smith, Lynna C. Kletke, Monica. (2004)

Adult growth hormone deficiency: current trends in diagnosis and dosing.

Source Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology. 17 Suppl 4:1307-20.

McGauley, G A. (1989) Quality of life assessment before and after growth hormone treatment in adults with growth hormone deficiency.Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica - Supplement. 356:70-2; discussion 73-4.

McMillan, C V. Bradley, C. Gibney, J. Healy, M L. Russell-Jones, D L. Sonksen, P H. (2003) Psychological effects of withdrawal of growth hormone therapy from adults with growth hormone deficiency.Clinical Endocrinology. 59(4):467-75.

Mukherjee, A. Tolhurst-Cleaver, S. Ryder, W D J. Smethurst, L. Shalet, S M. (2005)

The characteristics of quality of life impairment in adult growth hormone (GH)-deficient survivors of cancer and their response to GH replacement therapy.

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 90(3):1542-9.

Neely, E K. Rosenfeld, R G. (1994) Use and abuse of human growth hormone. Source Annual Review of Medicine. 45:407-20.

Stouthart, P J H M. Deijen, J B. Roffel, M. Delemarre-van de Waal, H A. (2003) Quality of life of growth hormone (GH) deficient young adults during discontinuation and restart of GH therapy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 28(5):612-26, 2003 Jul.

Version 1.0 First Published October 2007

Click

on these links to visit our Journals:

Psychiatry

On-Line

Dentistry On-Line | Vet

On-Line | Chest Medicine

On-Line

GP

On-Line | Pharmacy

On-Line | Anaesthesia

On-Line | Medicine

On-Line

Family Medical

Practice On-Line

Home • Journals • Search • Rules for Authors • Submit a Paper • Sponsor us

All pages in this site copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-