The use of the flexible bronchoscope for stenting malignant airway obstruction in the UK.

MJ Ledson, PDO Davies.

Tel: 0151 228 1616 Fax: 0151 228 5539

Correspondence to Dr PDO Davies.

|

The use of the flexible bronchoscope for stenting malignant airway obstruction in the UK. |

MJ Ledson, PDO Davies. |

The Cardiothoracic Centre,

Thomas Drive, Liverpool, L14 3PE, UK. Tel: 0151 228 1616 Fax: 0151 228 5539 Correspondence to Dr PDO Davies. |

Introduction

Patients with distressing, sometimes life threatening dyspnea due to a malignant large airway obstruction can now be palliated by the use of airway stents. This work was begun by Harkins in 1952 who used a metal alloy tube to relieve tracheal stenosis (1).By the 1960s Montgomery had designed his T-shaped silicone stent which was placed with the patient under general anaesthesia. The stent side arm exited via a tracheostomy to enable the patient to introduce a suction catheter, as secretion retention was a serious problem due to the impaired mucocilliary clearance. This side arm could be occluded by the patient making speech possible (2). Other silastic stent designs followed including the use of Y-shaped stents for lesions beyond the carina (3). By the 1990s Dumon had published the results of his silastic stent (4), which was made of moulded silicone and had regularly placed studs on its external surface to reduce displacement. A general anaesthetic was still required for placement using the rigid bronchoscope after laser treatment and/or dilation had restored a lumen.

Self expanding wire stents have been designed for biliary, oesophageal and vascular use (5,6). These have been modified for use in the bronchial tree and two types can be inserted using the flexible bronchoscope and therefore are in common use in the UK.

The Wallstent (Schneider, Zurich, Switzerland) which is composed of filaments of a cobalt based alloy braided in the form of a tubular mesh.

The Gianturco stent (Cook Europe, Denmark), which is made from a continuous loop of stainless steel in a double coil format of zig zag wire. The proximal and distal extremities of the wire have small hooks that anchor into the airway wall. Because of its design the Gianturco stent excerpts greater strut pressure on airway walls than the Wallstent (7).

Insertion techniques

Both stents come in a variety of sizes and both can be inserted using a flexible bronchoscope and local anaesthesia (8,9,10,14). Once the lesion has been visualised, a guide wire is passed via the biopsy channel through the malignant narrowing. The bronchoscope is removed, the loading catheter is fed over the guidewire and through the narrowing. The guide wire is removed and the stent is pushed to the distal end of the loading catheter using the supplied trocar. Radiopaque skin markers or fluoroscopy or both are used to position the stent. Alternatively the stent can be placed under direct vision using the flexible bronchoscope (10) (Figures 1-4).

Benefits

Most patients with malignant central airway obstruction present late and are in such distress that urgent stent placement is necessary. This makes it difficult to obtain objective measurement in improvement in well being and lung function. Tojo measured lung function in 5 out of 25 patients with a malignant tracheobronchial stenosis (3 Gianturco, 2 Wallstent), all showed improved spirometry post stenting (8). A study using the Wallstent in 27 patients showed stenting improved the Karnofsky index, WHO dyspnea score and spirometry (11), and a study using the Gianturco stent has shown improvement in the Karnofsky index, Medical Research Council dyspnea score, visual analogue scores for breathing and well being and spirometry (10).

In the UK these stents are used to palliate distressing dyspnea (Fig 4). There is no significant differences in survival between the two stents, with survival ranging from 77-135 days (8,10,11,12).

Possible complications.

Migration

Migration of these stents is seen more commonly in benign than malignant stenoses. However in malignant disease the Wallstent has higher reported migration rates 22-83% (11,13), than the Gianturco stent 0-4% (10,12). This is due to the absence of hooks and a reduced strut pressure (7).

Intra-luminal tumour progression

Theoretically tumour can grow through the metal latticework of bare metal stents and re-occlude the lumen of the airway. This occurred in up to 44% (4/9) of patients in small studies (8,14) but larger studies of 56 patients found no evidence of this (10). Because of this risk, some authors recommend bare metal stents should only be used in extra luminal tumour compression and covered stents should be used where intraluminal tumour is found (8). The Gianturco stent has been modified by the addition of a silicone covering (8,15), and the Wallstent is available with a polyurethane covering (Schneider, Zurich, Switzerland. Certainly a covered stent is required if a fistula is present (15,16,19).

Mucous plugging

Covered metal stents interfere with the normal mucociliary clearance mechanisms of the bronchial tree. The use of large drop aerosols has been advocated to help clear secretions. Bare metal stents rapidly become epitheliised and incorporated into the bronchial wall, with cellular covering being visible by the third week, allowing normal mucociliary clearance to occur (17).

Vascular and Airway perforation.

Perforation of the vascular wall has been reported with Gianturco stents when used in benign disease (18), and pneumothorax requiring a chest drain in up to 3% of patients with malignant disease (10). Vascular and airway perforation has not been described with the Wallstent.

Summary

The primary aim in the palliation of malignant large airway obstruction is to relieve dyspnea quickly with minimal distress to the patient, and to relieve the obstruction for such a period of time so that the patient succumbs to the underlying malignancy without the need for further bronchoscopic intervention.

Metal stents have the great advantage over silicone stents in that they can be placed quickly under local anaesthetic using the flexible bronchoscope, greatly increasing the number of centres in the UK who are able to offer this service. Also if a wire stent is placed and overlies a lobar orifice, this area is not epithelised and will not cause occlusion of the lobar bronchi. Finally metal stents can also be combined with other palliative treatments such as chemotherapy, laser therapy, and external or endobronchial radiotherapy.

The Gianturco stent because of increased strut pressures and anchoring hooks is less likely to migrate than the Wallstent, but is more likely to cause airway or vascular perforation. Thus the choice of which of these stents to use is down to the clinicians personal preference.

There is no doubt that patients with malignant large airway obstruction can obtain great relief from stent placement, and ongoing refinement of stent design will continue to improve this vital form of palliative therapy.

Illustrations

Figure 1 |

|

| Chest X-Ray showing complete collapse of the left lung. |

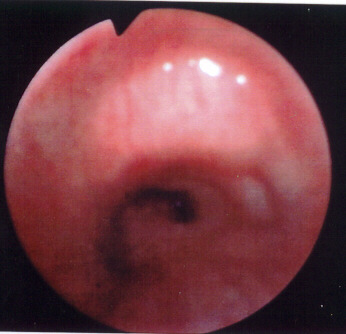

Figure 2 |

|

Bronchoscopic appearance of the near total occlusion of the left main bronchus. Sufficient lumen is available to feed a guide wire through the obstruction. |

Figure 3 |

|

A Gianturco stent has been deployed. Clearly visible is the double coil format of zig zag wire. The stent will continue to slowly expand for up to 24 hours. |

Figure 4 |

|

The Gianturco stent is visible in the left main bronchus and the left lung is re-expanding. |

References.