Browse through our Journals...

The reliability of asymmetrical thigh creases in the diagnosis of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: is there a need for referral to a paediatric unit?

1. Stephen Cooke (corresponding author)

2. David Miller

3. Jonathan Gregory

4. Andrew Roberts

5. Nigel Kiely

Research carried out at the Robert Jones & Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital.

Keywords

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

Asymmetrical thigh creases

Diagnosis

Screening

Summary

It is a commonly held belief, both amongst health care professionals and the lay public that asymmetrical thigh creases (ATC) in an infant is a sign of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). This study aims to determine whether this finding alone is sufficient to warrant referral to a specialist paediatric orthopaedic surgeon. The outcome of all patients referred to our unit with ATC as the sole reason for referral was retrospectively analysed. 187 such children were identified. One required a Pavlik harness, 2 had closed reductions and application of hip spicas and one underwent innominate osteotomy. Of these 4 patients, 3 had other clinical signs identified when examined by a specialist. The positive predictive value of ATC alone for the diagnosis of DDH requiring treatment is 2% for general practitioners and 0.5% for specialist children’s orthopaedic surgeons. We conclude that the finding of thigh crease asymmetry in the absence of other risk factors or clinical signs should not warrant specialist referral for consideration of DDH.

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a term covering a spectrum of conditions ranging from subtle acetabular dysplasia to frank dislocation. Depending on the definition used, the incidence quoted in the literature varies from 0.1% to 10% with approximately 1.2 per 1000 live births requiring treatment for DDH in the Western world (Donaldson and Feinstein, 1997).

There are several features of DDH that make screening problematic, however risk factor assessment along with clinical examination of all infants at birth and at six weeks of age is currently recommended by the UK screening council (UK National Screening Committee, 2006). One such examination finding is asymmetry of the thigh creases (ATC). The correlation between the finding of ATC and DDH has been questioned, some authors suggesting a strong link (Stoffelen et al, 1995, Omeroglu and Koparal, 2001, Abu Hassan and Shannak, 2007) and others questioning its use (Stein-Zamir et al, 2008, Dogruel et al, 2008). In our region, the finding of ATC on routine screening prompts referral by the health visitor to the patient’s general practitioner. In some cases, patients are referred on to a specialist children’s orthopaedic surgeon in the absence of any other risk factors or clinical signs. This study was designed to audit the number of children referred to our unit where ATC was the sole reason for referral. The outcome of these patients was studied to determine the effectiveness of this policy.

Methods and Aims

The electronic patient records of all patients referred to our unit between January 2003 and May 2008 were reviewed. All patients in our hospital have complete records, prospectively gathered in an electronic database. The inclusion criterion was infants referred for DDH to our institution with the finding of ATC in the general practitioner referral letter. Patients were excluded if any other clinical findings or risk factors were present. All patients were seen in the outpatient department and assessed both clinically and radiologically by a paediatric orthopaedic consultant. If the child was less than six months of age, they underwent dynamic ultrasound of the hip and if six months or older a pelvic radiograph was done.

Results

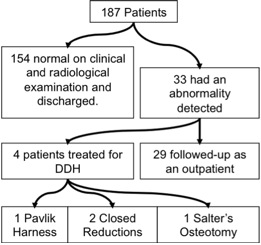

187 patients (80 boys and 107 girls) met the inclusion criteria. The mean age at the time of referral was 8.6 months (range 2 to 18 months). Of these 187 children, 154 (82%) were found to be normal after specialist clinical examination and ultrasound or x-ray. Thirty three (18%) had some evidence of DDH, 29 of which had mild acetabular dysplasia that resolved without treatment. 4 patients (2%) were treated for DDH, 1 in a Pavlik harness, 2 with closed reduction and hip spica and 1 with open reduction and Salter’s osteotomy (Figure 1). Three of these patients, when examined by a specialist, were found to have additional clinical findings, therefore only 1 patient with ATC alone required intervention. The outcome of all 4 of these patients at their most recent follow-up was excellent (Severin class 1).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram illustrating the outcome of all patients included in the study.

Discussion

Our results show that the positive predictive value (PPV) of ATC as the sole clinical finding for DDH requiring treatment is 2% (4 of 187). When those patients not treated but followed-up for mild acetabular dysplasia are included, this rises to 18% (33 of 187). Interestingly, of the 4 children treated for DDH, 3 had additional clinical findings when examined by a specialist (limitation of abduction in all cases with 1 patient also having shortening on Galeazzi testing). This observation is supported by other studies noting the significant effect of the experience of the examiner (Myers et al, 2009). Therefore only 1 out of 187 referred patients was diagnosed with DDH where ATC was the only finding after specialist review (PPV 0.5%). This patient underwent a Salter’s innominate osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia but was not dislocated at presentation. The proposed mechanism accounting for thigh crease asymmetry is concertinering of the soft tissues due to a shortened limb. If the limb lengths are equal, as they were in this case, it is likely that the observation of ATC was coincidental.

The variability reported in the literature regarding the association between ATC and DDH may be due to ATC being a somewhat subjective finding. Bias will be introduced by the fact that some specialists who are inclined to believe in its effectiveness may report very minor asymmetry as definite ATC, whereas those convinced that it is not useful may regard the same asymmetry as normal and therefore not record it. A limitation of this study is that only one of the consultants examined each patient. Ideally more than one person should examine each child independently at each review and/or take clinical photographs to document the asymmetry.

This study looked specifically at patients who were referred for DDH where ATC was the sole reason for referral. ATC is a common clinical finding in the general population, affecting approximately 13% of all children (Rosegger et al, 1990). In children with diagnosed DDH, ATC is found in up to 73% of cases presenting between 3 and 7 months of age (Abu Hassan and Shannak, 2007). These statistics imply a high sensitivity and low specificity, a fact confirmed by a study looking at the reliability of clinical examination in the detection of ultrasonically diagnosed DDH (Dogruel et al, 2008). Other research has found that history and examination combined is more effective, with 67% of children with at least 2 risk factors and 1 positive finding on examination having DDH. It was asserted that ATC was associated with a four times higher risk of DDH. 5 patients, from a population of 188 infants referred to a specialist center, were specifically identified as being diagnosed with DDH with ATC as the only clinical finding. It is not mentioned whether these patients had any risk factors in the history or the reason for their initial referral (Omeroglu and Koparal, 2001). We are not aware of any study looking at the predictive value of ATC alone as a referral trigger.

None of the 29 patients followed up for dysplasia went on to deteriorate or require any form of treatment. They required a total of 48 out-patient appointments (in addition to their index referral), 20 dynamic ultrasound scans and 32 x-rays, costing an estimated £13,000. There is a great deal of uncertainty regarding which patients with acetabular dysplasia will progress and which will resolve. It is estimated that 80-90% of so-called ‘immature’ hips do not require treatment (Barlow, 1962, Falliner et al, 1999). In our unit, all patients under 6 months who have suspected DDH undergo dynamic ultrasound carried out by both a radiologist and assessment by a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon. The results of this method have been audited and found to be very reliable (Kiely, unpublished observations). This may explain why none of these 29 patients were later treated for DDH. The acetabular cartilage angle is a new method which may further improve our predictive power. It has been demonstrated to have a 96% PPV when used in conjunction with patient age and acetabular index (Zamzam et al, 2008). It has the advantage of being effective in children as young as 2 months although does require a formal arthrogram, precluding its use as a universal screening tool.

Conclusion

The finding of an asymmetrical thigh crease alone is an unreliable clinical sign in the diagnosis of DDH, with only 0.5% of such patients going on to require treatment. Careful risk factor assessment and clinical evaluation is recommended to reduce unnecessary referrals and consequent parental anxiety. Where ATC is the only clinical abnormality with no risk factors for DDH, primary care physicians and other healthcare professionals can be reassured that the risk of DDH is minimal.

Affiliations

Author 1 (corresponding author)

The Hospital for Sick Children

555 University Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M5G 1X8

Canada

Tel: (Canada) 416 951 4912

e-mail: s.j.cooke@virgin.net

Author 2

Leighton Hospital

Middlewich Road

Crewe, Cheshire

CW1 4QJ

United Kingdom

Authors 3 to 5

Robert Jones & Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital

Oswestry

Shropshire

SY10 7AG

United Kingdom

References

1. Donaldson JS and Feinstein KA. (1997) Imaging of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatric Radiology. 44, 591-615.

2. UK National Screening Committee. (2006) The UK NSC policy on Developmental dislocation of the hip screening in newborns. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/hipdislocation. Accessed 31st May 2009.

3. Omeroglu H & Koparal S. The role of clinical examination and risk factors in the diagnosis of DDH (2001) Arch Orhop Trauma Surg. 121, 7-11.

4. Abu Hassan FO and Shannak A. (2007) Associated risk factors in children who had late presentation of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Journal of children’s orthopaedics. 1, 1863-2521.

5. Stoffelen D, Urlus M, Molenaers G and Fabry G. (1995) Ultrasound, radiographs and clinical symptoms in developmental dislocation of the hip: a study of 170 patients. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 4, 194-9.

6. Stein-Zamir C, Volovik I, Rishpon S and Sabi R. (2008) Developmental dysplasia of the hip: risk markers, clinical screening and outcome. Pediatrics International. 50, 341-5.

7. Dogruel H, Atalar H, Yavuz OY and Sayli U. (2008) Clinical examination versus ultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip. International Orthopaedics. 32, 415-9.

8. Myers J, Hadlow S and Lynskey T. (2009) The effectiveness of a programme for neonatal hip screening over a period of 40 years: a follow-up of the New Plymouth experience. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br). 91-B, 245-8.

9. Rosegger H, Rollett HR and Arrunategui M. (1990) Routineuntersuchung des reifen neugeborenen. Inzidenz haufiger “kleiner befunde”. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 102, 294-9.

10. Falliner A, Hahne HJ and Hassenpflug J. (1999) Sonographic hip screening and early management of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 8, 112-7.

11. Barlow TG. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip (1962) Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br). 44-B, 292-301.

12. Zamzam MA, Kremli MK, Khoshhal KI, Abak AA, Bakarman KA, Alsiddiky AM and Alzain KO. Acetabular cartilaginous angle (2008) A new method for predicting acetabular development in developmental dysplasia of the hip in children between 2 and 18 months of age. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 28, 518-23.

Copyright © Priory Lodge Education Ltd. 2010

First Published June 2010

Click

on these links to visit our Journals:

Psychiatry

On-Line

Dentistry On-Line | Vet

On-Line | Chest Medicine

On-Line

GP

On-Line | Pharmacy

On-Line | Anaesthesia

On-Line | Medicine

On-Line

Family Medical

Practice On-Line

Home • Journals • Search • Rules for Authors • Submit a Paper • Sponsor us

All pages in this site copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-