|

|

|

|

|

|

MILESTONES OF PSYCHOSOCIAL ONCOLOGY IN CANADA: REFLECTIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR THE FUTURE

Barry D. Bultz, Ph.D., C.Psych. Director, Department of Psychosocial Resources, Tom Baker Cancer Centre, and Adjunct Professor and Chief, Division of Psychosocial Oncology, Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Published in Giornale Italiano di Psico-Oncologia, 2005 (issue 1), (republished online and authorized by Il Pensiero Scientifico, Rome)

ABSTRACT – We repot the initiatives and the policy of the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO) both in terms of psychosocial morbidity secondary to cancer, of strategy for cancer control in Canada and of prevention of distress through its rapid recognition (distress as the 6th Vital Sign)

Background Geographically, Canada is the second largest country in the world (next to Russia) with an area of 9,984,670 square kilometers. Ten provinces and three territories make up this country that is overseen by a federal (national) government. Health care in Canada is directed by the principle that all Canadians should have equal access to care irrespective of where they live. Simply stated, Canadians and the Canadian Government hold to the principle that: health care is a right, not a privilege and that health care should be provided free of charge to all Canadians. Having outlined our guiding principle—why then do gaps exist in the services available to Canadians? Why do some cancer care facilities support the development of psychosocial oncology programs and the recruitment of psychosocial oncology professionals while other facilities do not? While the principle of universal health care is embraced by provincial and federal governments, budget constraints and the politics of medicine remains at the heart of the debate. Canadian cancer care practitioners claim that survival and extension of life are the primary considerations and given early, better diagnostics and more effective drugs are required. Physicians talk about quality of life, but clearly the primary driver (if not the only driver) is biomedical care. Psychosocial care of the cancer patient remains the new kid on the block—and in reality a 20-year-old kid at that.

Goals of this Status Report Given the opportunity of reflecting on psychosocial oncology in Canada, I will provide an overview on:

Cancer Care in Canada Approximately 50 years ago, provinces began speaking of the special needs of cancer patients. For those touched by the disease at that time, a cancer diagnosis most certainly meant pain and suffering, surgery, radiation or chemotherapy and a shortened lifespan accompanied by significant emotional distress and challenges to the quality of life. Fifty years ago, the poor prognosis and a belief that patients should not be told of their cancer diagnosis drove the cancer care agenda away from the need to provide psychosocial care. The belief was that if nothing could be done, patients should be protected from feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. This perspective was not only a Canadian philosophy of care; it was a universal perspective with physicians ascribing to a sense of paternalism (given the lack of knowledge about communication research or psychosocial issues). Given the poor prognosis and the call for the specialization of cancer care, cancer hospitals began surfacing. In Canada, the Alberta’s Cancer Act was first proclaimed in 1941 stating that all cancer treatments and drugs would be provided without charge As a result, the provincial government mandated that Albertan cancer patients were to receive cancer care (including chemotherapy and radiation therapy) at no cost. Since Canada provides for a universal health plan, what happens in one province tends to be followed to some degree in all Canadian jurisdictions. Unfortunately, despite the evidence, psychosocial care is often seen by cash-strapped cancer programs as "soft" and often not considered as part of the essential clinical service requirement. Psychosocial care in the United States often does not fit the agendas of "for-profit" cancer centres, hospitals and insurance companies. Psychosocial professionals looked to this resistance as an impetus to come together and formed The Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO). This organization allows psychosocial professionals to support each other collegially, share our science, and attempt to be present at the decision table whenever and wherever oncology is discussed.

The Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO) The impact of emotional distress as well of the benefits of psychosocial care on the patient and family began to be recognized in the 1970s and resulted in considerable interest and growth of psychosocial oncology. The works of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross and Dame Sicily Saunders, for example, can be credited with opening the door for psychosocial oncology to be introduced to cancer care because the issues of emotional distress were being so clearly identified as vital in palliative care. Clearly, it was very shortly after we began hearing Kubler-Ross talk about moving from Anger to Depression to Acceptance that more psychosocial research (from time of diagnosis across the complete cancer trajectory) began being referenced. By 1983, Canadian psychosocial oncology professionals began searching each other out informally and with a mindset to discover what psychosocial oncology programs were taking place in other cancer centres across the country. The number of psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers practicing in Canada at that time were few, with most working in isolation. Not only were these professionals limited in number, but also there were no benchmarks, little science, and no journals. This sense of professional isolation—as well as a desire to learn more about the science, education, and practice of psychosocial oncology—created a call for a national association to serve as a common voice for those interested in the emerging field of psychosocial oncology. Subsequently, in April 1985 the Psychosocial Department in the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Calgary (with encouragement from colleagues in Toronto, Ottawa, Winnipeg, Edmonton and Vancouver) held the inaugural psychosocial oncology meeting of what would become CAPO. Since that time, CAPO has elected a slate of officers, created a newsletter offering information on research, courses, etc., held annual general meetings, and hosted an international conference. With a charter, by-laws and an executive in place, CAPO set out on its long road of advocacy work towards having a voice on how psychosocial care would and should be delivered. CAPO began by urging the Canadian Cancer Society (CCS) to begin funding psychosocial oncology research. It is important to note that the CCS is one of the most widely respected and recognized advocacy programs and not-for-profit fundraising and research granting agencies in Canada. The goal was to have the emotional perspectives of the cancer patient and their family recognized with regard to board functions, research and patient services. This required a major paradigm shift from this most powerful of agencies which previously had had a biomedical-oriented board of decision- and policy-makers. Due to the urging of patients (mostly breast cancer patients and survivors) and groups like CAPO, the psychosocial agenda now appears on virtually every forum, CAPO and the psychosocial needs associated with cancer patients are represented on key national committees. Noteworthy accomplishments of CAPO are many:

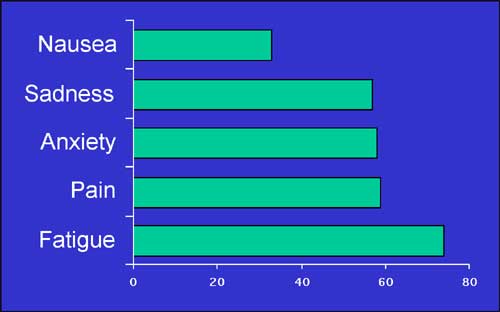

Table 1 Symptom Prevalence among Cancer Patients (1)

Patients (%)

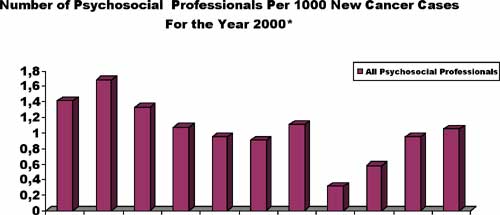

Psychosocial Resources in Canada Psychosocial oncologists (2-5) have known for many years that the prevalence of emotional distress in cancer patients is high and complex and can be explained scientifically. From a number of international studies (6-8, 5) looking at the prevalence rates alone it appears that emotional distress ranges from 35% to 70%. The issue of workload and professional resources available to cancer patients is important. In Canada, medical and radiation oncologists believe that a ratio of one oncologist to roughly 215 patients is seen as optimal for good practice. In 1999, a survey of every cancer centre across the Canada was conducted (9) to ascertain numbers of psychosocial professionals (as defined a core disciplines according to the CAPO Standards). The survey recognized that though the whole medical team (physicians, nurses, chaplains and volunteers) are supportive of cancer patients’ needs, it was the sub-specialty of psychosocial oncology that the survey sought to capture statistics on— specifically, the numbers of psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers employed by Canadian cancer centres to treat the emotional needs of cancer patients. The survey portrayed surprising and disturbing findings:

This survey (9) demonstrated that the lack of psychosocial human resources in oncology care is a critical nation wide problem in Canada—not because financial resources are lacking, but rather because the will of traditional medicine to value the human side of cancer simply has not been present. Given this rather disappointing and obvious fact, a national human resources standard and plan of action for all disciplines related to cancer care (with psychosocial being one of the programs being considered) is needed. The task is by no means small.

Canadian Association of Provincial Cancer Agencies/Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control Predictions are clear that cancer rates will rise significantly. A call for action was made by health care practitioners and the Canadian Ministry of Health to answer the question of how Canada will handle this rapid increase. As a result two national organizations were formed. In 1999, the Canadian Association of Provincial Cancer Agencies (CAPCA) was established and for the first time psychosocial oncology was included. It was an organization made up of provincial leaders (CEOs and cancer centre directors) and advisory discipline leaders (from medical oncology, radiation oncology, nursing, medical physics, psychosocial oncology, etc.) Around the same time, the Canadian Government’s Ministry of Health established The Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control to look at issues related to the looming health care crisis in Canada. The primary goals of this working group were to:

This forward-looking group also established a Psychosocial Advisory Committee. Clearly, psychosocial oncology was seen as a valuable player in the cancer care delivery system, and as a core program requiring attention. While these successes are noteworthy, additional dollars to support professional resources for cancer patients and their families will be the real indicator of just how successful psychosocial oncology will be in the political arena of policy and resource allocation. Given the limited resources available in health care, arguments about burden of cancer and cost-benefits of psychosocial care seems at times to have fallen on deaf ears. Changing medical systems is a challenge; however increasing knowledge of psychosocial issues facing cancer patients and their families has been a primary focus of CAPO.

The next Step: Emotional Distress: the 6th Vital Sign

In June 2004, a proposal before the Advisory Council of the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control moved to endorse Emotional Distress a the 6th Vital Sign. Without question, this endorsement will signal a change for how cancer patients will be seen. No longer can the emotional issues facing cancer patients be marginalized. As a vital sign (along with the physical vital signs of pulse, heart rate, blood pressure, respiration and pain— the 5th Vital Sign), it will be incumbent on cancer care providers to explore issues related to emotional distress. With the support of the Canadian Strategy of Cancer Control and others, an International Consensus meeting is planned for 2005 to help in the selection of a psychosocial distress-screening tool that we, in Canada will attempt to implement in all cancer centres. With the endorsement of this 6th Vital Sign, the next logical step is to screen for emotional distress leading to a moral imperative to treat where required (10, 11). Most certainly this will in turn demand greater resources and better care for our cancer patients and their families—a victory for our patients, our science and our discipline-clearly the next step in the growth and development of psychosocial oncology, not only in Canada, but globally.

References

1) Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology 1999. Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology Standards. CAPO: Toronto. 2) Cella D. 1998. Factors influencing quality of life in cancer patients: Anemia and fatigue. Semin Oncol 25, 43-46. 3) Zabora J, Blanchard CG, Smith ED, et al. 1997. Prevalence of psychological distress among cancer patients across the disease continuum. J Psychosoc Oncol 15: 73-86. 4) Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al. 2001. Prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology 10:19-28. 5) Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. (2004). High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 90: 2297-2304. 6) Grassi L, Sabato S, Rossi E, et al. 2004. Psychosocial implications of cancer: A study by using the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR) {Abstract]. Psycho-Oncology 13 (Suppl): S54-S55. 7) Akizuki N, Nakano T, Okamura M, et al. 2004. Development of the impact thermometer added to the distress thermometer as a brief screening tool for adjustment disorders and/or major depression in patients with cancer [Abstract]. Psycho-Oncology 13 (Suppl): S47. 8) Khatib J, Salhi R, Awad G. 2004. Distress in cancer in-patients in King Hussein Cancer Centre (KHCC); A study using the Arabic Modified Version of the Distress Thermometer [Abstract]. Psycho-Oncology 13 (Suppl): S58. 9) Bultz BD. 2002. Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology: Changing the face of cancer care for patients, community and the healthcare system. Report to the Romanow Commission on the Future of Healthcare in Canada. 10) Bultz BD. (2004) Emotional care takes centre stage [Editorial]. Oncology Exchange 3: 3. 11) Bultz BD, Holland J, Sepulveda C, et al. (2004) Psychosocial distress–the 6th Vital Sign: From identification to intervention [Abstract]. Psycho-Oncology 13 (Suppl): S56. |

|