Browse through our Journals...

When Research Fails to Inform: Current Treatments for Depressed Children in an Inpatient Setting

Misty M. Ginicola, Ph. D. and Christina Saccoccio, M. S.

Southern Connecticut State University

Yale University

Abstract

Efficacy research indicates that treatments for depressed youth have small or no effect and are laden with methodological problems. What choices then, do clinicians have when choosing treatments for depressed children in crisis? The purpose of the present study was to describe characteristics, types of treatments prescribed and the average treatment response upon discharge in 246 inpatient depressed children. Findings indicate that children were severely impaired and often comorbid with other disorders. Patients received a combination of therapy and medications, predominantly antipsychotics and antidepressants. Symptom presentation, gender and age were related to type of medication prescribed. The treatment effect and GAF scores indicate a small to no effect of interventions at discharge. Implications and recommendations for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Childhood depression has become a significant public health concern since 20% of all youth meet criteria for diagnosis of major depressive disorder by the age of 18 (Birmaher et al., 1996; Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley, & Andrews, 1993). This serious psychiatric disorder negatively affects mood, energy, interest, sleep, appetite and overall functioning in children. While these classical symptoms are often evidenced in adults, children present with additional symptoms of depression, such as irritability and aggression (American Psychological Association, 2000; National Institute of Mental Health, 2000). Depression is extremely pervasive as it affects every aspect of functioning, and is not just a transient phase a child experiences. The condition is serious as it often leads to recurrent episodes, drug abuse and even suicide in both adolescence and adulthood (Angold & Costello, 1993).

Suicide

Suicide is the third leading cause of death among teenagers (Arias, MacDorman, Strobino & Guyer, 2003; National Center for Health Statistics, 2001; United States Public Health Service, 1999). Childhood depression is often chronic, with almost three-fourths of depressed patients relapsing after treatment (Goldman, Nielsen & Champion, 1999). This condition can also be more complicated to treat in children because it is often comorbid with other disorders, most frequently anxiety and conduct-type disorders (Angold, Costello & Erkanli, 1999; Caron & Rutter, 1991; Rohde, Lewinsohn & Seeley, 1991). Comorbidity in psychiatric conditions is quite common; results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) study show that nearly half of all people with one mental disorder meet the criteria for two or more disorders, with 22% carrying two diagnoses and 23% carrying three or more (Kessler et al., 2003). Comorbidity is similar in children, where half of youth who receive mental health services in the United States have been diagnosed with a co-occurring disorder (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2002).

Why is depression in childhood so prevalent?

There are two primary reasons why the magnitude of childhood depression is persistent in those who are diagnosed: 1) variability in the availability of quality treatment in many regions; and 2) lack of research on what is empirically effective in children. When a child has depressive symptoms, they need access to effective treatment. In order to obtain such access, the family of a child with depression must be in close proximity to a qualified professional and must have financial resources to afford their services. In rural areas of the United States, not only do residents experience higher rates of poverty, they have access to fewer health care professionals, emergency psychiatric services, inpatient psychiatric facilities and specialized physicians (Wilhide, 2002). In 1997, approximately 40% of rural residents lived in areas where psychiatric care was severely limited; however, only 12% of the metropolitan population experiences these types of shortages (Wilhide, 2002). The situation has become dire in over 3,500 localities, which have been designated by the federal government as crisis areas (United States Public Health Service, 2000).

No matter where the depressed child is located or what type of financial resources to which they have access, the child will not improve unless they are given an effective treatment. Currently, the accepted types of treatment for children with depression are psychotherapy and/or pharmaceutical interventions. Unfortunately, the literature on the effectiveness of these treatments remains sparse (Vitiello & Jensen, 1997). When examining peer-reviewed English-language studies from 1990, there have only been 22 studies on the efficacy of psychotherapy and 13 on psycho-pharmaceuticals in the treatment of childhood depression.

Lack of research

One of the main reasons why there are so few studies in this area is due to the sensitive nature of trying untested pharmaceuticals and techniques on children; this poses some complicated ethical considerations for researchers. Without research-based knowledge of treatment efficacy and possible negative side-effects, untested treatments for children are extremely dangerous. A researcher cannot guarantee a participant’s safety, as these drugs have many side effects in adult populations. Other issues affecting the number of published studies are common problems associated with psychiatric samples: non-compliance and drop-out rates. Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) found a mean drop-out rate of 47% across 125 studies of psychotherapy efficacy, while Delaney (1998) found more than one-third of psychiatric appointments go unattended. Non-compliance in antidepressant studies is also extremely high (Buchanan, 1992; Keller, Hirschfeld, Demyttenaere & Baldwin, 2002; Qurashi, Kapur & Appleby, 2006). Studies have reported that up to 70% of patients demonstrate non-compliance by discontinuing medication, failing to fill prescriptions or skipping medication dosages (Katon et al., 1995; Melfi et al., 1998). High drop-out rates among psychiatric patients is also concerning; meta-analyses have shown participant attrition ranging from 21 to 33% regardless of drug class (Anderson & Tomenson, 1995; Bollini, Pampallona, Tibaldi, Kupelnick & Munizza, 1999; Montgomery & Kasper; 1995).

In addition to these research barriers, exclusion criteria in depression treatment efficacy trials are often excessively rigorous. In a survey of 18 clinical antidepressant trials, nearly 80% of patients did not meet inclusion criteria, disqualifying them from participation (Bielski & Lydiard, 1997). When considering treatment efficacy for youth depression, the standards are even more restrictive; one such study (Emslie et al., 2002) dedicated a page-long table to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The most commonly used psychiatric exclusion criteria in antidepressant efficacy trials are short duration of depressive episode, suicide risk and the presence of another Axis I disorder (Zimmerman, Chelmniski, & Posternak, 2004). Exclusion is also extensive in studies on the impact of therapy and includes many of the same criteria (TADS, 2004). In a review of 33 studies on treatment for youth depression since 1990, other common exclusion criteria included taking psychotropic medications prior to study, risk of pregnancy, and low IQ. Exclusionary criteria are used in treatment efficacy trials to ensure a high level of internal validity; however, failing to recognize the importance of external validity, or generalizability to patients in the real-world, is as serious of an issue as failing to control for all variables within a study.

While the exclusion of bipolar patients and short depressive episodes is advantageous, the exclusion of those with suicide risk and other comorbid disorders severely limits the generalizability of these studies. In a review of 29 studies on treatment for youth depression since 1990, almost 80% of studies excluded patients with a comorbid Axis I disorder and 34% excluded patients at suicidal risk (Cohen, Gerardin, Mazet, Purper-Ouakil & Flament, 2004; Cheung, Emslie & Mayes, 2005; Weisz, McCarty & Valeri, 2006). This finding is problematic since 79% of individuals with major depressive disorder have another comorbid psychiatric diagnosis (Kessler et al., 2003). When comparing the participant pool within these studies to those patients seen in real clinical practice, one realizes that participants treated in efficacy trials “represent a minority of patients treated for major depression (Zimmerman, Mattia, & Posternak, 2002, p. 469).”

The situation is even worse when we consider the applicability of these study’s findings to youth in crisis: those who are admitted to inpatient facilities. In meta-analyses of treatment for youth depression, only one study sampled from an inpatient population (Cohen et al., 2004; Cheung et al., 2005; Weisz et al., 2006). Youth inpatient samples are rarely used in depression treatment efficacy studies because they are perceived as not being representative of the population; however, the number of children actually treated in inpatient facilities has been seriously underestimated. According to The United States Department of Health and Human Services (2000), of children and adolescents using mental health care, 22% were admitted to inpatient services. This percentage translates to 286,176 children admitted to inpatient facilities; inpatient facilities are always at maximum capacity with hospitalization rates continuing to rise (Geller & Biebel, 2006). Contrary to what many believe, children receiving inpatient services represent a huge population in need of effective and tested treatment.

Of equal concern are the demographics of patients included in studies of youth treatment for depression. More often than not, age and race of patients do not represent real-world clinical profiles of depressed youth. In meta-analyses of depressive treatment efficacy, only 8 studies included children under 10 and only 3 more studies included preadolescents under the age of 13 (Cohen et al., 2004; Cheung et al., 2005; Weisz et al., 2006). In addition, the vast majority (70%) of studies included in meta-analyses either did not report race or contained Caucasian samples of 70% or higher (Cohen et al., 2004; Cheung et al., 2005; Weisz et al., 2006). Furthermore, only eight studies included 100 or more patients in their trials which seriously questions the generalizability of the other efficacy studies (Cohen et al., 2004; Cheung et al. 2005; Weisz et al., 2006).

Despite the problems with generalizability, the effectiveness of treatment within these studies is still important. However, meta-analyses of both psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions for childhood depression concluded that overall, treatments either fail to improve symptoms significantly compared to placebo or their effect size was incredibly small and of little practical significance (Kirsch, Moore, Scoboria & Nicholls, 2002; Weisz et al., 2006). When compared to treatments for other psychopathological conditions, “youth depression treatment does not surpass but instead may lag significantly behind treatment for other youth conditions (Weisz, et al., 2006, p. 143).”

Results indicate that psychotherapy is not a highly effective treatment for depressed youth, with a mean effect size (ES) of 0. 34, which is a small to medium effect (Weisz et al., 2006). Additionally, the effects of psychotherapy are found to be short-term and did not persist past one year (Weisz et al., 2006). Clearly, while current psychotherapies have some impact on childhood depression, they are quite limited in their strength, breadth and permanence (Weisz et al., 2006). These findings strongly question the practical and clinical significance of using psychotherapy with depressed children.

In terms of the research on pharmaceutical interventions, results indicate that this type of treatment is completely inadequate for depressed youth. Although several antidepressants are now being used on this population, only Fluoxetine has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in pediatric depression (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2004). There is little known however, on the efficacy of antidepressant medication in children; prior to 1997 there were no published studies showing placebo to be more effective than antidepressants and to date there have been no placebo-controlled trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on children alone (Cheung et al., 2005; Safer & Zito, 2006). In two meta-analyses (Cohen et al., 2004; Cheung et al., 2005) of the efficacy of SSRI and tricyclic antidepressants on depression in children, authors found placebo-comparison response rates to range from 2 to 26% across trials for SSRIs and absolutely no positive effect for tricyclic medications. However, when self-report measures are used to indicate symptom severity, there are no significant differences between SSRI and placebo groups. In addition to the problems with drop-out and mortality rates mentioned earlier, many studies are flawed in other ways, including miscalculations on depression scale ratings and effect size reports (Cheung et al., 2005). Cheung and colleagues conclude that “clinicians are obligated to make their own interpretations of the limited data available” in order to best help their young depressed client (Cheung et al., 2005, p. 752).

Not only have studies reported a lack of efficacy for these medications, some studies have actually reported a high frequency of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) from SSRI use in children; the most prevalent being activation (restlessness and hyperactivity), insomnia, somnolence (sedation and drowsiness) and gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting (Safer & Zito, 2006). Other studies have described typical adverse physical and behavioral symptoms including mania, hypomania, hostility, suicidality, aggression, motor restlessness, agitation and impulsivity (Braconnier, Le Coent & Cohen, 2003; Cheung et al., 2005; Emslie et al., 1997; Leonard, March, Rickler & Allen, 1997). Given the possible link between antidepressants and their treatment-emergent AEs in children, it has been suggested that patients and clinicians turn to other means of treatment first and use antidepressants with extreme caution (Hampton, 2004; United States Food and Drug Administration, 2004).

One study investigated the impact of combining CBT and an SSRI (TADS, 2004) in depressed children. The authors reported a significant effect of the combination therapy from CBT alone, SSRI alone and placebo; however the effect size was small. Additionally, there were variable results across all measures; a suicidal ideation measure did not indicate any significant differences between groups. Furthermore, 84% of recruited participants were excluded from the study before it began; once the study was underway, there was also an 18% drop-out rate.

Perhaps most troubling is the potential link between antidepressants and increased suicidality in children and adolescents. In October 2003, the FDA issued a ‘Public Health Advisory’ warning physicians of increased suicidal ideations and attempts among pediatric patients treated with antidepressants (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2003). Despite some criticism of the trial, two independent, FDA-commissioned re-analyses of the data showed that antidepressants nearly doubled the risk of suicide-related events compared with placebo (Leslie, Newman, Chesney & Perrin, 2005; Tonkin & Jureidini, 2005). By 2004, the FDA instructed manufacturers to include a warning on all antidepressants about the associated risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2004).

Like the use of antidepressants, the use of antipsychotics in children has increased dramatically over the past decade, especially the use of atypical antipsychotics (Olfson, Marcus, Weissman & Jensen, 2002; Patel, Crismon, Hoagwood & Jensen, 2005). In children, atypical antipsychotics are used for a variety of problems, not necessarily linked to psychosis; these include behavior problems, conduct disorders, developmental disabilities, obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as bipolar and depression (Campbell, Rapoport & Simpson, 1999; Howland, 2005; Kelly, Love, Mackowick, McMahon & Conley, 2004; Rawal, Lyons, MacIntyre & Hunter, 2004). A year-long study (Curtis et al., 2005) of commercially ensured youths in the United States showed that nearly one fourth of children taking antipsychotic medications were aged nine years or younger and were primarily male (80%). Despite their increasing prevalence, the only antipsychotic medication approved by the FDA for use in children is Risperidone with Autistic children only (FDA, 2006). Although long-term effects of these agents on children are unknown, serious short-term side effects have been reported from use of atypical antipsychotic agents including neuroleptic malignant syndrome, extrapyrimidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, weight gain, hyperglycemia, new-onset diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular abnormalities, hyperprolactinemia and even death (DuBois, 2005; Kelly et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2005; Schur et al., 2003). Current data (Findling, 2003) suggests that children and adolescents are at higher risk than adults for experiencing sedation, acute extrapyramidal side effects, withdrawal dyskinesia and significant weight gain while taking atypical antipsychotics. The lack of sufficient testing and the potentially harmful side effects of atypical antipsychotics on children make it a problematic treatment option (Correll et al., 2006). There are absolutely no investigations on the efficacy of antipsychotics for treatment of depressed youth; additionally, nothing is known on how prescribing antipsychotic medication for a comorbid disorder affects youths who also have depression. Nor has there been any investigation on how anti-psychotics may interact with anti-depressant medication in children.

Given that psychotherapy, antidepressants, and antipsychotics have not been proven completely effective in treating pediatric depression in a research setting, what are clinicians to prescribe for their patients? If empirical research, which uses participants who are more likely to respond to treatment (i.e. older children with no comorbid psychological or medical disorders), has not been able to find a successful treatment, then what is happening in inpatient settings for children in crisis? The goal of the present study is to describe the demographics and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses of children entering inpatient treatment for depression within an urban university hospital setting and to discuss the type of treatments used within this real-world inpatient setting. The following are the main research questions for the present study:

1) What are the demographics of children being admitted to an inpatient setting?

2) What types of treatments are being used in this setting for children with depression?

3) Under what circumstances are the treatments being prescribed?

4) What is the average treatment response within these children?

Method

Participants

Participants were 246 current or past patients within a children’s inpatient university hospital from 2000 to 2006. The psychiatric inpatient service is a 15-bed facility that provides comprehensive psychiatric, psychosocial and educational evaluation for children aged 4 to 16. Children are typically referred from the emergency room at the university hospital, but can also come from other local hospitals which have no room in their inpatient facilities. Children have also been referred from schools and parents. This data was part of a larger study investigating the relationship between mental age and depressive symptoms (Ginicola, 2006).

Participants were predominantly male (n = 149) and of Caucasian descent (n = 135). However, the sample was representative of other ethnicities, including African American (n = 54), Hispanic (n = 46), Multi-racial (n = 10), and Asian (n = 1). Participants’ ages ranged from 4 to 16 years old, with an average of 10.33 (SD = 2.42) years. Approximately half of the sample (n = 117) was receiving Title 19 medical insurance, which is indicative of being below poverty level. Approximately 20% (n = 43) of the sample were involved with the Connecticut Department of Children and Families, indicating they had been removed from their homes due to suspicion or confirmation of abuse.

Measures

Demographics, Diagnostic and Prognostic Data

All children’s demographic information was obtained through their individual record or the hospital database. In addition, the database contained information on comorbid diagnoses and readmissions. Depressive symptoms, using DSM-IV (APA, 2000) definitions, were established by reviewing each patient's complete record and noting their presence. Symptoms were presented in various ways throughout the child's record; records typically included checklists of symptom presentation upon admission, daily notes and a discharge summary. Depressive symptoms were noted as either present or absent within the record; inter-rater reliability among the four raters involved in the project was established at 93% (κ =. 86). Additionally, the children’s discharge records included their Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score upon release from the hospital.

Psychiatric Response

Treatment response measures are typically given to participants; however, many studies cite the importance of using clinician reports as well (Corruble, Legrand, Zvenigorowski, Duret & Guelfi, 1999). Although clinician judgment alone is not enough to identify the severity of depression, they are the current standard for identifying response and changing treatment when necessary (Hickie, Andrews & Davenport, 2002). Clinician’s judgments on the responses to treatment were well-detailed within the patient’s discharge records. In the present study, three scales were used, which were based on Clinical Global Impression and Clinical Global Impression of Improvement Likert scales; these scales have been used in clinician report measures of depression previously (Khan, Khan, Shankles & Polissar, 2002; Mulder, Joyce & Frampton, 2003; Wilhelm et al., 2004). The present study used a 3-point remission scale, in which 0 represented no response, 1 represented partial remission, and 3 represented full remission. The second was a 6-point response scale in which -2 represented a worse response, -1 somewhat worse, 0 unchanged, 1 somewhat improved, 2 greatly improved response, and 3 completely resolved. These scales have been validated with the Hamilton Depression ratings scale and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Within this study, the inter-rater reliability among the four raters established for the three-point scale was 99.86% (κ =. 996) while the inter-rater reliability established for the six-point scale was 99.4% (κ =. 990). The scales showed high concurrent validity (r = .83, p<.001).

Procedure

The list of patients admitted to the psychiatric hospital since the year 2000 was reviewed to identify all children with depressive diagnoses. These participants were then screened for IQ scores and the child's discharge report of the first admission to the hospital was identified and reviewed. All demographic, diagnostic, and prognostic data were noted either through the record review or by searching the hospital patient record computer database. Information on the child's readmissions (total number and date of first readmissions) was recorded later from the hospital's database. Four raters reviewed all information and recorded their rating scores.

Results

Who are the children in inpatient facilities?

As reported within the method section, participants were varied, but were predominantly male and Caucasian; many of these children would be considered at-risk, being in either extreme poverty and/or victims of abuse and neglect. These children were also highly disturbed. Although there was extremely high variability between individual patients’ length of stay in the facility (ranged from 1 to 272 days), participants’ mean length of stay was 29.74 (SD = 36.45; Mdn = 17) days. Many participants (30%) were admitted to the hospital more than once. Of these children, readmissions ranged from 1 to 8, with an average of 2 (SD = 1.28) times.

Table 1

Diagnoses for Depressed Participants

Diagnostic Category |

n |

% |

|

|

|

254 |

100% |

|

Major Depressive Disorder |

27 |

11. 0% |

Major Depressive Episode |

15 |

3. 2% |

Major Depressive Disorder, with psychotic features |

32 |

13. 0% |

Dysthymia |

7 |

2. 8% |

Depressive Disorder, NOS |

93 |

37. 8% |

Mood Disorder, NOS |

80 |

32. 5% |

Anxiety |

97 |

33. 3% |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

9 |

4. 0% |

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder |

6 |

2. 8% |

Panic Disorder |

1 |

0. 4% |

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

61 |

22. 3% |

Separation Anxiety Disorder |

1 |

0. 4% |

Anxiety Disorder, NOS |

19 |

7. 4% |

Conduct / Behavioral |

124 |

50. 3% |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

53 |

21. 6% |

Conduct Disorder |

5 |

2. 0% |

Oppositional Defiant Disorder |

44 |

17. 8% |

Disruptive Behavior Disorder, NOS |

12 |

4. 9% |

Intermittent Explosive Disorder |

7 |

2. 8% |

Impulse Control Disorder, NOS |

3 |

1. 2% |

Cognitive |

31 |

12. 6% |

Autism Spectrum |

1 |

0. 4% |

Mental Retardation |

8 |

3. 3% |

Learning Disability |

19 |

7. 7% |

Language Disorder |

3 |

1. 2% |

Other |

49 |

21% |

Adjustment Disorder |

1 |

0. 4% |

Anorexia Nervosa |

1 |

0. 4% |

Borderline Personality Disorder (or Traits) |

7 |

4. 0% |

Conversion Disorder |

1 |

0. 4% |

Dissociative Disorder NOS |

1 |

0. 4% |

Drug Induced Psychosis |

1 |

0. 4% |

Eating Disorder, NOS |

2 |

0. 8% |

Enuresis, Nocturnal |

2 |

0. 8% |

Psychotic Disorder, NOS |

21 |

8. 6% |

Reactive Attachment Disorder |

5 |

2. 0% |

Trichotillomania |

1 |

0. 4% |

Tic Disorder |

3 |

1. 2% |

Tourette’s Disorder |

3 |

1. 2% |

Table 2

Percentage of Depressed Participants Experiencing Individual Depressive Symptoms

Depressive Symptom |

n |

% |

|

|

|

Aggressive Behavior |

192 |

78. 0% |

Depressed Mood |

186 |

75. 6% |

Diminished Ability to Concentrate |

38 |

15. 4% |

Disinterest or Apathy |

147 |

59. 8% |

Eating Changes |

56 |

22. 8% |

Feelings of Guilt |

20 |

8. 1% |

Feelings of Worthless and Hopelessness |

72 |

29. 3% |

Irritability |

179 |

72. 8% |

Physical Lethargy or Fatigue |

87 |

35. 4% |

Psychomotor Changes |

142 |

57. 7% |

Sleeping Changes |

102 |

41. 5% |

Thoughts of Death and Suicidal Attempts |

178 |

72. 4% |

Table 3

Treatment Type by Presence of Participant Symptoms

Depressive Symptom |

Individual Therapy |

Family Therapy |

Group Therapy |

c2 |

p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aggressive Behavior |

75% |

73% |

66% |

1. 42 |

>. 05 |

Depressed Mood |

82% |

77% |

81% |

0. 77 |

>. 05 |

Diminished Concentration |

13% |

13% |

11% |

0. 25 |

>. 05 |

Disinterest or Apathy |

64% |

58% |

68% |

1. 66 |

>. 05 |

Eating Changes |

20% |

19% |

23% |

0. 40 |

>. 05 |

Guilt |

9% |

10% |

13% |

0. 58 |

>. 05 |

Irritability |

75% |

72% |

66% |

1. 65 |

>. 05 |

Physical Lethargy or Fatigue |

40% |

36% |

40% |

0. 37 |

>. 05 |

Psychomotor Changes |

61% |

56% |

64% |

1. 66 |

>. 05 |

Sleeping Changes |

41% |

40% |

40% |

0. 06 |

>. 05 |

Suicidal Ideations / Attempts |

69% |

78% |

77% |

2. 19 |

>. 05 |

Worthless / Hopelessness |

28% |

31% |

45% |

4. 84 |

>. 05 |

Table 4

Medication Type by Presence of Participant Symptoms

Neither n = 33 |

Antipsychotic n = 83 |

Anti-depressant n =49 |

Both Meds n = 81 |

c2 |

p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aggressive Behavior |

82% |

93% |

53% |

77% |

28. 74 |

<. 01 |

Depressed Mood |

64% |

66% |

90% |

82% |

13. 36 |

<. 01 |

Diminished Concentration |

18% |

15% |

14% |

16% |

0. 32 |

>. 05 |

Disinterest or Apathy |

52% |

54% |

65% |

65% |

3. 70 |

>. 05 |

Eating Changes |

27% |

22% |

29% |

19% |

2. 21 |

>. 05 |

Guilt |

9% |

1% |

14% |

11% |

8. 82 |

<. 05 |

Irritability |

67% |

84% |

61% |

70% |

9. 76 |

<. 025 |

Physical Lethargy or Fatigue |

42% |

42% |

22% |

33% |

6. 12 |

>. 05 |

Psychomotor Changes |

70% |

74% |

35% |

51% |

22. 73 |

<. 001 |

Sleeping Changes |

46% |

40% |

39% |

43% |

0. 56 |

>. 05 |

Suicidal Ideations / Attempts |

70% |

60% |

88% |

78% |

14. 48 |

<. 01 |

Worthless / Hopelessness |

24% |

17% |

47% |

33% |

14. 60 |

<. 01 |

As shown in Table 1, almost 70% of depressed children experienced their disorder in a non-traditional way: being diagnosed with either Depressive Disorder NOS or Mood Disorder NOS. Less often they were diagnosed with MDD or MDD with psychotic features. The vast majority of participants (76%) were also comorbid for other diagnoses. When considering the most common comorbid disorders: 66% were comorbid for an anxiety or conduct disorder (25% for an anxiety disorder, 29% for a conduct disorder and 12% for both an anxiety disorder and a conduct disorder). Thirteen percent of the sample also had some form of developmental or cognitive disability. The number of disorders for each child ranged from 1 to 5, with an average of 2 (SD = .99) disorders. Most of the depressed children within this sample presented with aggressive behavior, sadness, irritability, and suicidal ideations or attempts (See Table 2).

Also common were apathy and changes in psychomotor patterns.

What types of treatments are being used for children with depression?

Within this setting there were a variety of treatment options available for patients with depression: milieu, individual, group, family and pharmacological therapy. Milieu therapy was incorporated into the setting and included providing all (n = 246) children with structure, individualized supervision, basic behavior modification strategies and clinical staff support. In addition to the basic milieu, almost half (46%) were participating in active individual therapy sessions with a clinician. The content of this therapy varied to meet the child’s individual needs, but was comprised predominantly of CBT. Group (23%) and family (37%) therapy were less common, but also individualized to patient’s needs. Psychotropic medications were used with the majority of patients (95%); the children who were not prescribed medication were refused such by the patient’s parents or noted by clinicians to have sub-threshold symptoms. In one case, the patient was pregnant so medications were withheld. Children were prescribed between 0 and 13 medications, with an average of 2.5 (SD = 1.68) medications. The median number of medications prescribed to these children was 2.

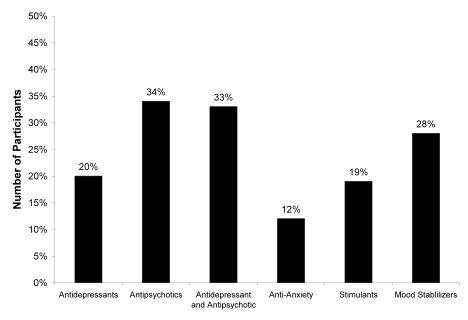

Figure 1. Percentage of participants receiving medication by type.

In terms of medication types, depressed children were prescribed a variety of medication types, as shown in Figure 1. Children were most commonly given either antipsychotics (67%) and/or anti-depressants (55%). When children were prescribed antipsychotic medication, patients were usually given atypical antipsychotics (59%), although some children were receiving typical antipsychotic medication (1%) or a combination of both (7%). The second most common medication prescribed to the depressed patients was anti-depressants, including SSRIs (47%), Tricyclics (2%), Aminoketones (3%) and a combination of two or more of the above (3%). Either in addition to or in few cases instead of (7%) antidepressant and antipsychotic medication, children were prescribed anti-anxiety, stimulants or mood stabilizers / anti-convulsants. Eighteen percent of children had their medications changed within the hospital, with a range of 1 to 5 medications (M = 1.61, SD = 0.97) being discontinued. The majority of discontinued medications were stimulants (39%) and antipsychotics (38%), followed by antidepressants (32%), mood stabilizers (18%), antianxiety (11%) and ‘other’ medications (9%). The most common reasons cited for discontinuing medications was the presence of an AE or the absence of an obvious treatment effect.

Under what circumstances are the treatments being prescribed?

Difference in therapy assignment was evaluated by investigating the symptom presentation in children who were given some combination of individual (n = 114), family (n = 90) and/or group (n = 56) therapies. As shown in Table 3, there was no relationship between the symptom presentation and the therapy assigned. This indicates that the choice of what type of therapy to give each client is dependent on other factors than depressive symptoms.

Difference in medication prescription was also evaluated by investigating the symptom presentation in those children who were given antipsychotics (n = 83), anti-depressants (n = 49), both medications (n = 81) or neither (n = 33). As presented in Table 4, large and significant differences can be seen for several symptoms. This suggests that the decision in regards to treatment is dependent on symptom presentation, as one would expect. Antipsychotics were prescribed more often when a child presents with predominantly irritability, aggression and psychomotor changes (most often psychomotor agitation). Anti-depressants were given more often to children presenting with more depressed mood, guilt, suicidal ideations or attempts, as well as feelings of worthlessness. However, both antipsychotics and anti-depressants were given to a large number of children. It appears that the decision to give both types of medication concurrently occurs when all symptoms are high – both externalizing behavioral types of symptoms (aggression, irritability, psychomotor) and classical internalizing symptoms (sadness, guilt, hopelessness and suicidal ideations and attempts).

In terms of comorbidity, the children assigned to receiving individual, group or family therapy as one of their treatments were not significantly different in terms of their comorbid disorder, χ2 (4) = 5.87, p >.05. However, the children who were receiving antipsychotics were more likely to present with a comorbid conduct disorder (82%) than the other psychotropic categories (neither 71%; anti-depressant 54%; both 42%), χ2 (6) = 29.05, p = 0.001.

Considering the demographics of participants, no differences were seen between type of therapy and gender, χ2 (2) = 0.13, p >.05. Additionally, the mean ages of children receiving each therapy type was 10 years old, indicating no relationship to age. However, Antipsychotics were prescribed more often to males (40%) than to females (24%); likewise, anti-depressants were prescribed more often to females (30%) than to males (13%), χ2 (3) = 14.41, p = 0.01. There were not large differences in the neither (females 10%; males 15%) and both (females 36%; males 31%) medication categories. There was also a significant difference between prescription type and the age of the patient, F (3,242) = 17.56, p < .001. An LSD post-hoc analyses indicate that children receiving no medication (M = 9.88; SD = 3.04) and antipsychotic medication (M = 9.07; SD = 2.36) were significantly younger than patients receiving anti-depressant medication (M = 11.53; SD = 2.03) or both (M = 11.10; SD = 1.69), p < .05.

How are these children responding to their individualized treatment?

Despite clinician’s best efforts to provide the best treatment, mean responding rates were incredibly low on each scale: 3-point scale was 0.73 (SD = .52); 6-point scale was 0.83 (SD = 1.05). These scores indicate that on average, children had improved slightly, but were not even in partial remission.

Additionally, the mean GAF score for all participants at discharge was 45.75 (SD = 8.34). This indicates that on average, children left the hospital with a serious impairment in social or school functioning. The scores ranged from 20 to 70, revealing that some children still had an inability to function upon release. Five percent of the participants scored below a 25, with 25% of the sample scoring below a 40 (indicating consistent major impairment). Those with the highest GAF scores (above 60; also 5%) still indicated a minor impairment in functioning.

The relationship between several child characteristics and psychiatric response and outcome were evaluated via a serious of t-tests. All variables (gender, minority status, DCF status, Title 19 status, presence of a comorbid disorder or the presence of a comorbid conduct disorder) were not significantly related to any of the outcome variables, p > .05.

Discussion

There is no question that children admitted to inpatient facilities are predominantly at-risk children and are all in crisis. The children within this study were no different: half of the children were in extreme poverty and one-fifth had been removed from their homes for alleged or founded abuse. The children within this study stayed a mean of 30 days within the inpatient setting, although many children stayed significantly longer. The vast majority, 75%, of these children were comorbid for another disorder, most frequently an anxiety or conduct disorder.

The results of this study suggest that in addition to the treatment milieu, children were placed in a therapeutic context: individual, group and/or family therapy. Individual therapy sessions were present in approximately half of the depressed sample; whereas, group and family therapy were less common. Assigning a child to a type of therapy was not associated with their symptom presentation, their gender or age.

Although antipsychotics are not tested in children and anti-depressants are not recommended due to their increase in suicidal thoughts, the majority of children received one of these medications or both in combination. Children were more likely to be prescribed antipsychotics when they presented with externalizing symptoms; these children were also more likely to be males. Conversely, anti-depressants were prescribed more often for children presenting with internalizing symptoms, which also happened to be females. It is also of import that the children receiving antipsychotics were, on average, 2 years younger than children receiving antidepressants. This is of great concern because there is no data on the impact of antipsychotics on depressed children, much less those who are only 9 years old. Although the majority of children receiving antipsychotics presented with a comorbid conduct disorder, a significant portion (28%) did not. After prescription, nearly one-fifth of participants had medications discontinued within the inpatient setting; either they were discontinued because of non-response or adverse side-effects. Despite the myriad of treatments offered to these children in crisis, children’s responses were little to none. Patients were still presenting with severe symptoms and severely impaired functioning.

The findings of this study support the previous research that indicates current techniques for depressed youth are inadequate (Cheung et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2004; Weisz et al., 2006). However, despite the small effect sizes of psychotherapy (most commonly cognitive-behavioral therapy; CBT) and pharmacological interventions, the majority of depressed children are being given these treatments in the absence of better interventions (Kirsch et al., 2002; Weisz et al., 2006). More frighteningly, a large percentage of children are being given antipsychotics for many disorders other than psychosis, despite its lack of testing on children (Curtis et al., 2005; Jensen et al., 1999; Pappadopulos et al., 2003; Snyder et al., 2002). Past research (Olfson, Marcus, Weissman & Jensen, 2002; Patel, Sanchez, Johnsrud & Crismon, 2002; Rappley et al., 1999; Zito et al., 2000) has revealed that antipsychotics are being prescribed throughout the nation for children at younger and younger ages. The fact that within this sample, we found a large percentage of depressed children, with and without comorbid conduct disorders, receiving antipsychotic medication is of concern.

Given the extensive restrictions, this study indicated that if an efficacy study only included children with MDD and no comorbid disorders in the absence of a serious suicidal threat, absolutely 0% of these inpatients would be eligible for their studies; likewise, no efficacy studies reviewed would be applicable for generalization to these children. This is a major problem within the literature; clinicians do not have an adequate research base to inform the treatment of severely depressed children. Depressed inpatient children, perhaps more than any other, are more at-risk for suicide completion and have more severe symptoms than their outpatient counterparts; these children are in crisis and in desperate need of effective interventions (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

When reviewing the treatment efficacy literature for depression, those in clinical practice receive a disheartening message; treatment for depression in children is either dangerous, untested or has an incredibly small effect. Clinicians are left empty-handed when it comes to helping their patients: children who are currently in pain, at risk for a multitude of later functioning problems and even death. In an inpatient setting, the clinician must choose between the lesser of two evils to keep the children from hurting themselves and hurting others. By experimenting with therapies and medications, the child may be put at greater risk for health and emotional problems, but something must be done to prevent them from causing damage. Given the nature of inpatient services, as soon as the child is judged as not in immediate crisis, they are sent home, many to return within a few days or years. However, research indicates the situation is grim in both outpatient and community settings, with treatment failing to work there as well (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

The present study is not without its limitations. This was a study of one inpatient setting: specifically, an urban university hospital. A larger study of more settings would better inform medication and treatment trends throughout the nation. Even given this limitation, however, the setting where this research was performed is of incredible quality, with educated staff and access to extensive research and other resources through its university connections. If the situation for depressed youth is troublesome in a setting such as this, it can be argued that it is probably worse at a great many other settings which do not have access to the same resources.

In order to improve the efficacy of treatment for children with depression, three recommendations for future research are made. First, alternative types of treatment must be investigated. The use of art, music and pet therapy has been prevalent in certain sects of clinical practice, but published evidence is typically qualitative in nature (Finn, 2003; Gold, Voracek & Wigram, 2004; Hanselman, 2001; Jorm et al., 2006). Large-scale, in-depth quantitative investigations of alternative types of therapy should be employed as the current treatments are not nearly effective enough for this population. Second, we, as a field, cannot continue to ignore the importance of research on inpatient depressed populations. These are the children most in need of help, but also most in need of adequate research on which to base treatment decisions. Finally, given that numbers for these types of studies are small and are likely to remain so, and given the ethical quandaries of performing experimental research on young children, the field must be open to studies other than those with high internal validity based on finding empirically-based treatments. These types of studies severely limit the generalizability of the findings to those it is designed to help, inpatient or outpatient. Being open to using mixed populations and qualitative studies is necessary in this situation. Case studies of children who recovered from depression and remained resilient after in-patient and/or out-patient treatment would also be of great import.

Childhood depression is not simple and clean; it is complex and chaotic. It is comorbid with many other disorders and may not cleanly fit into the DSM-IV categories for MDD, as it does in adults. But, these children are depressed and in need of significant help. Clinicians do not have the tools with which to help children with depression; and if the field continues to rely on highly constricted empirically-based treatment studies, they never will.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed. Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author.

Anderson, I. M., & Tomenson, B. M. (1995). Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants: A meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 310, 1433-1438.

Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (1993) Depressive comorbidity in children and adolescents: Empirical, theoretical, and methodological issues. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1779-1791.

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Erkanli, A. (1999) Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40, 57-87.

Arias, E., McDorman, M. F., Strobino, D. M., & Guyer, B. (2003). Annual summary of vital statistics—2002. Pediatrics, 112(6), 1215-1230.

Bielski, R. J., & Lydiard, R. B. (1997). Therapeutic trial participants: Where do we find them and what does it cost? Psychopharmacological Bulletin, 33, 75-78.

Birmaher, B., Ryan, N. D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Kaufman, J., Dahl, R. E., & Nelson, B. (1996). Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1427-1439.

Bollini, P., Pampallona, S., Tibaldi, G., Kupelnick, B., & Munizza, C. (1999). Effectiveness of antidepressants. Meta-analysis of dose-effect relationships in randomized clinical trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 297-303.

Braconnier, A., Le Coent, R., & Cohen, D. (2003). Paroxetine versus clomipramine in adolescents with sever major depression: A double-blind, randomized, multicenter trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 22-29.

Buchanan, A. (1992). A 2 year prospective study of treatment compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 22, 787-797.

Campbell, M., Rapoport, J. L., & Simpson, G. M. (1999). Antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(5), 537-545.

Caron, C., & Rutter, M. (1991). Comorbidity in child psychopathology: Concepts, issues and research strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32, 1063-1080.

Cheung, A. H., Emslie, G. J., & Mayes, T. L. (2005). Review of the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in youth depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(7), 735-754.

Cohen, D., Gerardin, P., Mazet, P., Purper-Ouakil, & Flament, M. F. (2004). Pharmacological treatment of adolescent major depression. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 14(1), 19-31.

Corell, C. U., Penzner, J. B., Parikh, U. H., Mughal, T., Javed, T., Carbon, M., & Malhotra, A. K. (2006). Recognizing and monitoring adverse events of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacology, 15(1), 177-206.

Corruble, E., Legrand, J. M., Zvenigorowski, H., Duret, C., & Guelfi, J. D. (1999). Concordance between self-report and clinician’s assessment of depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 33, 457-465.

Curtis, L. H., Masselink, L. E., Ostbye, T., Hutchison, S., Dans, P. E. Wright, A., Krishnan, R. R., & Schulman, K. A. (2005). Prevalence of atypical antipsychotic drug use among commercially insured youths in the United States. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 362-366.

Delaney, C. (1998). Reducing recidivism: Medication versus psychosocial rehabilitation. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 36, 28–34.

DuBois, D. (2005). Toxicology and overdose of atypical antipsychotic medications in children: Does newer necessarily mean safer? Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 17(2), 227-233.

Emslie, G. J., Rush, A. J., Weinberg, W. A., Kowatch, R. A., Hughes, C. W., Carmody, T., & Rintelmann, J. (1997). A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(11), 1031-1037.

Emslie, G. J., Heiligenstein, J. H., Wagner, K. D., Hoog, S. L., Ernest, D. E., Brown, E., Nilsson, M., & Jacobson, J. G. (2002). Fluoxetine for acute treatment of depression in children and adolescents: A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(10), 1205-1215.

Findling, R. L. (2003). Dosing of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 5(6), 10-13.

Finn, C. A. (2003). Helping students cope with loss: Incorporating art into group counseling. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 28(2), 155-165.

Geller, J. L., & Biebel, K. (2006). The premature demise of public child and adolescent inpatient psychiatric beds. Part I: Overview and current conditions. Psychiatry Quarterly, 77, 251-271.

Ginicola, M. M. (2006). A developmental approach to variability in depressed children’s symptomology. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Yale University.

Gold, C., Voracek, M., & Wigram, T. (2004). Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(6), 1054-1063.

Goldman, L. S., Nielsen, N. H., & Champion, H. C. (1999). Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14, 569-580.

Hampton, T. (2004). Suicide caution stamped on antidepressants. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(17), 2060-2061.

Hanselman, J. L. (2001). Coping skills interventions with adolescents in anger management using animals in therapy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, 11(4), 159-195.

Howland, R. H. (2005). Use of atypical antipsychotic agents in children and adolescents. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 43(8), 15-18.

Jensen, P. S., Bhatara, V. S., Vitiello, B., Hoagwood, K., Feil, M., & Burke, L. (1999). Psychoactive mediation prescribing practices for U. S. children: Gaps between research and clinical practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(5), 557-565.

Jorm, A. F., Allen, N. B., O’Donnell, C. P., Parslow, R. A., Purcell, R., & Morgan, A. J. (2006). Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for depression in children and adolescents. The Medical Journal of Australia 185(7), 368-372.

Katon, W., Von Korf, M., Lin, E., Walker, E., Simon, G. E., Bush, T., Robinson, P., & Russo, J. (1995). Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 273, 1026-1031.

Keller, M. B., Hirschfeld, R. M. A., Demyttenaere, K., & Baldwin, D. S. (2002). Optimizing outcomes in depression; focus on antidepressant compliance. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17, 265-271.

Kelly, D. L., Love, R. C., Mackowick, M., McMahon, R. P., & Conley, R. R. (2004). Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 14(1), 75-85.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R., Rush, A. J., Walters, E. E., & Wang, P. S. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095-3105.

Khan, A., Khan, S. R., Shankles, E. B., & Polissar, N. L. (2002). Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression rating scale, and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17, 281-285.

Kirsch, I., Moore, T. J., Scoboria, A., & Nicholls, S. S. (2002). The emperor’s new drugs: An analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Prevention and Treatment 5, Article 1. Retrieved December 6, 2006 from http://content. org/journals/pre/5/1/23.

Leonard, H. L., March, J., Rickler, K. C., & Allen, A. J. (1997). Pharmacology of the serotonin reuptake inhibitors in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 725-736.

Leslie, L. K., Newman, T. B., Chesney, P. J., & Perrin, J. M. (2005). The Food and Drug Administration’s deliberations on antidepressant use in pediatric patients. Pediatrics, 116, 194-204.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Hops, H., Roberts, R. E., Seeley, J. R., & Andrews, J. A. (1993). Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 133-144.

Melfi, C. A., Chawla, A. J., Croghan, T. W., Hanna, M. P., Kennedy, S., & Sredl, K. (1998). The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Achieves of General Psychiatry, 55(12), 1128-1132.

Montgomery, S. A., & Kasper, S. (1995). Comparison of compliance between serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants: A meta-analysis. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 9(4), 33-40.

Mulder, R. T., Joyce, P. R., & Frampton, C. (2003). Relationships among measures of treatment outcomes in depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 76, 127-135.

National Institute of Mental Health (2000). Depression. (NIH Publication No. 02-3561). Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

National Center for Health Statistics (2001). Death rates for 72 selected causes, by 5-year-groups, race and sex: United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Olfson, M., Marcus, S. C., Weissman, M. M., & Jensen, P. S. (2002). National trends in the use of psychotropic medications by children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(5), 514-521.

Pappadopulos, E., MacIntyre, J. C., Crismon, M. L., Findling, R., Malone, R. P., Derian, A., Schooler, N., Sikich, L., Greenhill, L., Schur, S. B., Felton, C. J., Kranzler, H., Rube, D. M., Sverd, J., Finnerty, M., Scott, K., Siennick, S. E., & Jensen, P. S. (2003). Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part II. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(2), 145-161.

Patel, N. C., Crismon, M. L., Hoagwood, K., & Jensen, P. S. (2005). Unanswered questions regarding a typical antipsychotic use in aggressive children and adolescents. Journal of Child and adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15(2), 270-284.

Patel, N. C., Sanchez, R. J., Johnsrud, M. T., & Crismon, M. L. (2002). Trends in antipsychotic use in a Texas Medicaid population of children and adolescents: 1996 to 2000. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 12(3), 221-229.

Qurashi, I., Kapur, N., & Appleby, L. (2006). A prospective study of noncompliance with medication, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior in recently discharged psychiatric inpatients. Archives of Suicide Research, 10, 61-67.

Rappley, M. D., Mullan, P. B., Alvarez, F. J., Eneli, I. U., Wang, J., & Gardiner, J. C. (1999). Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and use of psychotropic medication in very young children. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 153, 1039-1045.

Rawal, P. H., Lyons, J. S., MacIntyre, J. C., & Hunter, J. C. (2004). Regional variation and clinical indicators of antipsychotic use in residential treatment: A four-state comparison. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 31(2), 178-188.

Safer, D. J., & Zito, J. M. (2006). Treatment-emergent adverse events from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors by age group: Children versus adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 16(1/2), 159-169.

Schur, S. B., Sikich, L., Findling, R. L., Malone, R. P., Crismon, M. L., & Derivan, A., MacIntyre, J. C., Pappadopulos, E., Greenhill, L., Schooler, N., Van Orden, K., & Jensen, P. S. (2003). Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part I: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(2), 132-144.

Snyder, R., Turgay, A., Aman, M., Binder, C., Fisman, S., Carroll, A., & The Risperidone Conduct Study Group. (2002). Effects of Risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(9), 1026-1036.

Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) (2004). Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(7), 807-820.

Tonkin, A, & Jureidini, J. (2005). Wishful thinking: Antidepressant drugs in childhood depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 304-305.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). Section VI: National Mental Health Statistics. Children and adolescents admitted to specialty mental health care programs in the United States, 1986 and 1997. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2002, November). Report to Congress on the prevention and treatment of co-occurring substance abuse disorders and mental disorders. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

United States Food and Drug Administration (2003, October 27). Reports of suicidality in pediatric patients being treated with antidepressant mediations for major depressive disorder (MDD). Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

United States Food and Drug Administration (2004, March 22). FDA public health advisory: Worsening depression and Suicidality in patients being treated with antidepressant. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

United States Food and Drug Administration (2006, October 6). FDA approves the first drug to treat irritability associated with Autism, Risperdal. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

United States Public Health Service. (1999). The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent suicide. Washington, DC: Author.

United States Public Health Service (2000). Report of the surgeon general’s conference on children’s mental health: A national action agenda. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Vitiello, B., & Jensen, P. S. (1997). Medication development and testing in children and adults: Current problems, future directions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(9), 785-789.

Weisz, J. R., McCarty, C. A., & Valeri, S. M. (2006). Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 132-149.

Wierzbicki, M., & Pekarik, G. (1993). A meta-analysis of psychotherapy dropout. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24(2), 190-195.

Wilhelm, K., Kotze, B., Waterhouse, M., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Parker, G. (2004). Screening for depression in the medically ill: A comparison of self-report measures, clinician judgment, and DSM-IV diagnosis. Psychosomatics, 45(6), 461-469.

Wilhide, S. D. (2002, March 20). Rural health disparities and access to care. Paper presented to the Institute of Medicine Committee for Guidance in Designating a National Health Care Disparities Report by the National Rural Health Association, Washington, DC.

Zimmerman, M., Chelminski, I., & Posternak, M. A. (2004). Exclusion criteria used in antidepressant efficacy trials. Consistency across studies and repetitiveness of samples included. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(2), 87-94.

Zimmerman, M., Mattia, J. I., & Posternak, M. A. (2002). Are subjects in pharmacological treatment trials of depression representative of patients in routine clinical practice? American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 469-473.

Zito, J. M., Safer, D. J., DosReis, S., Gardner, J. F., Boles, M., & Lynch, F. (2000). Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283(8), 1025-1030.

First Published September 2011

Copyright Priory Lodge Education Limited 2001-

priory Useful links

Click

on these links to visit our Journals:

Psychiatry

On-Line

Dentistry On-Line | Vet

On-Line | Chest Medicine

On-Line

GP

On-Line | Pharmacy

On-Line | Anaesthesia

On-Line | Medicine

On-Line

Family Medical

Practice On-Line

Home • Journals • Search • Rules for Authors • Submit a Paper • Sponsor us

All pages in this site copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-