CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME (C.F.S.) IN A FAMILY OF DOGS

DIAGNOSIS AND

TREATMENT OF THREE CASES.

Walter Tarello, C.P. 42, 06061 Castiglione del Lago (PERUGIA) Italy. Email Author

CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME (C.F.S.) IN A FAMILY OF DOGSDIAGNOSIS AND

|

Walter Tarello, C.P. 42, 06061 Castiglione del Lago (PERUGIA) Italy. Email Author |

This work has been done in the Heron Veterinary Clinic of Castiglione del Lago (PERUGIA) Italy

A cluster of canine Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) was diagnosed according to current criteria accepted in human medicine. The fatigue and pain symptoms were associated with pyoderma, presence of micrococci-like organisms in the blood and the recovery of two vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus xilosus strains, from a pustule and from drinking water. Thiacetarsamide sodium, was administered intravenously at low dosage (0.1 mg/Kg/day) for three days in all dogs. Clinical and hematological parameters at days 4, 7 and 10 after therapy confirmed complete remission from the syndrome, which had lasted for more than 2 years and had been treated previously with several chemotherapeutics agents. The possible role of coagulase-negative staphylococci in the aetiology of CFS and the antimicrobial action of arsenicals are discussed.

Key-words: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, CFS, thiacetarsamide, dog, zoonosis.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), as originally defined by the American Centers for Disease Control and as recently redefined (Fukuda et al., 1994) is a human illness in which patients experience severe, debilitating fatigue for more than 6 months. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (NIAID, 1996) is defined by the presence of the following criteria:

• unexplained, persistent or relapsing chronic fatigue; • the concurrent occurence of 4 or more of the following symptoms, all of which must have persisted or recurred during 6 or more consecutive months of illness and must not have predated the fatigue: a) impairement in memory or concentration, b) sore throat, c) tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes, d) muscle pain or multijoint pain without swelling or redness, e) headaches, f) unrefreshing sleep, and g) postexertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours.

Most CFS cases are sporadic but, occasionally, close contacts, including family members, become ill with CFS at about the same time (Bell, 1994). Also, cluster of CFS-like illnesses have been reported during the past 60 years in various families and communities (NIAID, 1996).

Initial epidemiologic studies failed to identify a viral aetiology (Johnson, 1996) and recent advances seem to indicate a bacterial ethiology (Butt et al., 1998; Dunstan et al., 1999). During the past decade, substantial evidence has been generated to support the existance of a CFS-like illness among animals (Ricketts et al., 1992; Glass, 1998). Although Chronic Fatigue Syndrome has never been clinically described in dogs, prevalence surveys indicate that a remarkable number (97%) of patients with CFS had animal contact, particularly with dogs and cats, and that 75% of these pets appeared sick, with signs and symptoms which mimicked CFS in humans, strongly suggesting a zoonotic transmission (Glass,1998). A recent report describe CFS in horses: as with the disease in humans, Equine Fatigue Syndrome is associated with long-term exhaustion , difficult treatment and immune dysfunction (Ricketts et al., 1992).

Increased cariage of coagulase-negative Staphylococci (McGregor et al, 1998) has been found in humans with chronic pain/fatigue symptoms. The Staphylococci recovered from 89% of these patients produced membrane-damaging toxins, delta- and /or “horse”- haemolysins, whereas control subjects did not (Butt et al, 1998).

Recently, four horses diagnosed with CFS and resistant to standard therapies, were all found to carry unusual micrococci-like organisms in the blood (Tarello, 2000). Their CFS-resembling lethargy had a complete remission after a treatment with thiacetarsamide sodium (0.1mg/Kg/day IV) for 2-3 days. The clinical response was associated with the disappearance of micrococci from follow-up blood samples.

Little is known about the syndrome in animals and therefore, in this study, dogs fulfilling the current human criteria for CFS and resistant to extensive prior therapies were checked for similar blood abnormalities and therapeutical responses. The first aim of this paper is to report the clinical history, symptoms, microbiological findings and method of treatment in a cluster of dogs diagnosed with CFS. Information about environmental risk factors are given as partial explanation and importance of the presence of micrococci-like organisms in the blood is discussed.

Animal investigation.

The study comprised three related dogs with similar symptoms dominated by unexplained persistent fatigue and 5 other symptoms (muscle and multi-joint pain, sore throat, somnolence, postexertional malaise and lymphadenopathy) lasting more then 6 months. All dogs had relapsed after previous standard therapies that included several antibiotics (doxycycline, enrofloxacin, ceftazidime, amoxacillin + clavulanic acid), imidocarb, antihelmintics, vitamins and glucocorticoids. These animals were visited in their kennel during August 1994 to perform clinical and environmental examination and to collect blood samples for haematologic and serologic analysis. Drinking water for bacteriological examination was collected too. During additional visits, further clinical examinations were performed and blood samples were collected from the dogs at day 4, 7 and 10 after therapy.

Haematology

Complete blood counts (CBC) were performed on samples collected at the first visit (day 0) and at days 4, 7 and 10 after therapy. Two fresh blood smears, stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa and Wright techniques, were prepared each time . A Knott test for microfilariae was also performed at each visit.

Serology

Serum collected at day 0 was tested for circulating antigens of Dirofilaria immitis (Dirocheck ELISA) and antibodies against Lehismania donovani (Leishcan ELISA).

Biochemistry

Serum values of total protein (TP), albumin and globulin, serum CK and LDH were evaluated at days 0, 4, 7 and 10 after therapy. These values are summarized in table I and II.

Microbiology

Two swabs were taken, from drinking water and from an interdigital pustule of dog #1, immediately after the lesion was opened with a sterile needle. In both cases, sterile dry cotton- tipped swabs were placed into Brain-Heart infusion (bioMerieux) and incubated 24 h at 37oC. Under laminar-flux hood condition (MiniSecuritas, PBI) 10 microliters of the culture established from the drinking water were subcultured onto three different agar plates (Baird-Parker, CPS ID 2 and Muller-Hinton, bioMerieux) for 24 h at 37oC. Representative colonies were transplanted onto two more Muller-Hinton plates and submitted for identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing. Ten microliters of the culture established from the pustule were subcultured onto two separate Muller-Hinton 2 agar plates for identification (API-Staph, bioMerieux) + antibiotic sensitivity testing. All samples were subject to Gram stain and Catalase test.

Therapy

Thiacetarsamide sodium (Caparsolate,Abbott Laboratories) was administered intravenously at 0.1 mg/Kg/day for 3 days. No other medication was given.

Kennel investigation

The 3 dogs comprised in the study were 2 adult female Kurtzhaar and 1 juvenile male less than 3 months old, all living together in a cement-floored kennel subdivided into 2 runs, separated by chain-link fencing and covered with a tin roof. The adult females had been vaccinated and dewormed every year. The kennel has been built inside the area of a mushroom cultivation farm. All dogs had access to water coming from a well, situated near an artificial lake where the waters from the mushroom cultivation were discharged.

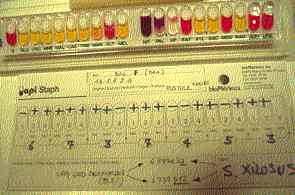

A sterile swab taken from the kennel’s water and immediately incubated into brain-heart infusion for 24 h at 37oC generated bacterial growth which was subcultured (10 microliters) onto three specific agar grounds for further 24 h. at 37oC. Gram positive and catalase positive cocci were identified in all three plates. Representative colonies from the Muller-Hinton plate revealed them to be (99.9%) Staphylococcus xilosus . This strain produced acid from mannitol, so it was considered pathogen. The bacteria showed a partial sensitivity to gentamycin and were not sensitive to spiramycin, kanamycin, amoxacillin, chloramphenicol, doxycycline, sulpha- trimethoprim and vancomycin.

|

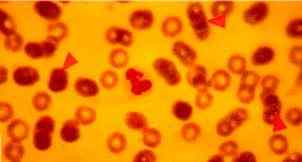

Figure One: Dog with CFS. Arrows indicate three micrococci, 0.3-0.5 micrometres in size, lying on the external surfaces of RBCs (x100) |

Dog #1. (See Figures Three and Four below) The first dog investigated was a 7-year old female Kurtzhaar, with chronic undefined illness lasting more than 2 years and resistant to extensive prior therapy. The symptoms were : episodic weakness, muscular pain, sore throat, exercise intolerance, periodic fever, weight loss, pyoderma, shedding and dull haircoat and lymphadenopathy. The dog had poor tolerance to moderate exertion and was reluctant to run for more than 1 minute.

Physical exam revealed tender and enlarged lymph nodes and poor body condition. Serology for Lehismania donovani, Dirofilaria immitis and the Knott test for microfilariae was negative. The CBC was unremarkable. Serum creatine kinase (CK= 188.8 IU/L) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH= 477.1 IU/L) were elevated (table I and II).

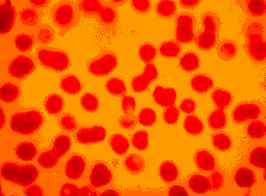

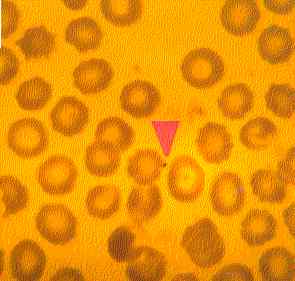

Material taken with a sterile swab from an interdigital pustule and immediately incubated in Brain- Heart infusion at 37oC for 24 h produced bacterial growth. These bacteria were then recognized as gram-positive and catalase-positive cocci after subculture (fig.3), identified as of Staphylococcus xilosus (99.8%, Api Staph bioMerieux) (fig. 4). This strain was also mannitol- fermenting. This strain was partially resistant to gentamycin, chloramphenicol, doxycyllin, sulpha- trimethoprim, amoxacillin and resistan to spyramicin, kanamycin and vancomycin (fig. 3). Examination of fresh blood smears stained with May-Grunwals-Giemsa were negative for babesiosis and ehrlichiosis, but small, micrococci-like organisms, 0.3-0.5mm in diameter, were found attached to the external surface of red blood cells (RBCs) in quantity varying from 10 to 15 % (Fig 1, 2 and 5). Thiacetarsamide sodium (0.1 ml/Kg/day) was given intravenously for three days.

In a few days the weakness decreased and interdigital pyoderma began to heal, the appetite improved leading to total weight gain and better locomotion.

A physical examination made at day 4 showed that general health status was improved. Creatine kinase activity was still high (CK=176.8 IU/L) and 2 fresh blood smears revealed a decreasing percentage of micrococci upon RBCs (2-5%).

The clinical response appeared satisfactory at day 7, when muscular pain and resistance to physical activity had ceased and pyoderma pustules had completely disappeared. Biochemistry examinations still revealed elevated activity of creatine kinase (CK= 291.8 IU/L). A reduced percentage of RBCs (1-5%) was carrying micrococci and the globulin fraction was rising (3.61 gr/dl).

At day 10, blood smears were micrococci-negative, creatine kinase (CK = 33.4 IU/L), lactate- dehidrogenase (LDH= 156.3 IU/L) activities and hematocrit (PCV= 41.2%) were now within the reference ranges. Following complete clinical remission, no exercise resistance could be observed, lymph node size were decreasing and the haircoat was bright.

Dog #2 This was a 7-year old female Kurtzhaar, the sister of dog #1, with a similar 2-year history of chronic illness , characterized by muscular pain, lethargy, sore throat, severe interdigital pyoderma, lameness, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, abundant scurf and shedding hairs and post- exertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours.

Serological and Knott’s testing proved negative for heartworm disease. Serum antibodies against Leishmania donovani were not detected. There was a normocytic normochromic anaemia (PCV= 31%, MCV = 64.9 fl., MCH = 22.04 pg) and all other laboratory examinations gave results within normal limits, with the exception of increased CK (380 IU/L) and LDH (449 IU/L) activities at rest.

Fresh blood smears showed 10% of RBCs with micrococci on their surface ( fig. 1, 2 and 5). Treatment was performed as usual with thiacetarsamide sodium in low dosage (0.1/ml/Kg) for three days.

At day 4 the PCV improved (35%), the CK reduced (75.4 IU/L) and decreased number of RBCs with micrococci were seen (5%). The dog was less reluctant to perform exercise and did not showed muscular pain on palpation.

At day 7, pyoderma and lameness had completely disappeared and smaller number of RBCs (2%) appeared parasitized by micrococci.

At day 10, the PCV was improved (36.5%) and the CK (41.0 IU/L) and LDH (211.5 IU/L)

activities were normal. A very low number of micrococci (0.5%) could be detected in fresh blood

smears . Physical examination revealed a complete recovery from weakness and exercise

intolerance, improved condition of the haircoat and moderate diminution of the peripheral lymph

nodes dimensions.

Dog #3 This was a 3 month-old pup of dog#2, affected since birth by lethargy, poor appetite and severe pododermatitis at all feet. The dog always had difficulty rising and was unable to climb stairs or to move faster than a clumsy walk. The puppy the smallest of the litter and was hand reared for the first month.

Two similarly affected littermates had to be put asleep previously. Despite a normal hematocrit, high muscle enzyme activity (CK= 182.8 IU/L) and presence of micrococci on 5-8% of RBCs were findings similar to those of the mother and her sister. Arsenical treatment was done as usual for three days. In the following week a second course was required in order to achieve a complete remission from the pododermatitis. Fresh blood smears resulted negative for micrococci and the puppy was able to play vigorously with the other littermates.

|

Table I |

DOG 1 |

||||

|

range |

exam |

day 0 |

day 4 |

day 7 |

day 10 |

|

38-55 |

PCV (%) |

37.0 |

38.0 |

34.7 |

41.2 |

|

5.7-7.7 |

TP (gr/dl) |

6.89 |

6.97 |

6.93 |

7.21 |

|

2.2-3.8 |

Alb. (gr/dl) |

3.58 |

3.34 |

3.32 |

3.32 |

|

1.7-3.9 |

Glob.(gr/dl) |

3.31 |

3.62 |

3.61 |

3.89 |

|

100< |

CK (IU/L) |

188.8 |

176.8 |

291.8 |

33.4 |

|

300< |

LDH (IU/L) |

477.1 |

- |

- |

156.3 |

|

absence |

micrococci |

10-15% |

2-5% |

1-2% |

0-1% |

|

Table II |

DOG 2 |

||||

|

range |

exam |

day 0 |

day 4 |

day 7 |

day 10 |

|

38-55 |

PCV(%) |

31.0 |

35.0 |

34.0 |

36.5 |

|

5.7-7.7 |

TP (gr/dl) |

6.50 |

6.49 |

6.78 |

6.43 |

|

2.2-3.8 |

Alb. (gr/dl) |

3.33 |

3.41 |

3.47 |

3.49 |

|

1.7-3.9 |

Glob.(gr/dl) |

3.17 |

3.08 |

3.31 |

2.94 |

|

100< |

CK (IU/L) |

380.0 |

75.4 |

43.9 |

41.0 |

|

300< |

LDH (IU/L) |

449.0 |

442.0 |

- |

211.5 |

|

absence |

micrococci |

10-12% |

5-6% |

0.5-1.0% |

0.0-0.5% |

|

Figure Two: Dog with CFS. A high number of micrococci can be seen on the external surface of RBCs (x100, May-Brunwald Giemsa stain). |

| Figure Three: Dog 1 affected by CFS and chronic pyoderma. Catalase positive vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus (Gram positive cocci) from and interfingers pustule. |  |

|

Figure Four: Dog 1. Very good identification (99.8%) of Staphylococcus xilosis .strain recoveedd from teh same interfinger pustule. |

| Figure Five: Dog with CFS. A micrococcus can be observed adhering to the external surface of a red blood cell (x100, May-Grunwald Giemsa stain). |  |

In the absence of a specific test, a diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) in human medicine is currently done by exclusion of other known fatigue-related diseases and by compliance with a clinical definition (Fukuda et al., 1994; NIAID, 1998; Dunstan et al.,1999). In this report, the dogs referred as having CFS apparently matched the official definition of CFS in humans (NIAID, 1996) and the clinical picture of CFS in horses (Ricketts et al., 1992; Tarello, 2000).

During the previous 2 years, these dogs had progressively deteriorated despite treatment with several antimicrobials. The primary features of fatigue and pain, were accompanied by chronic skin lesions and pyoderma, as occurs in 10-35% of human patients (Rebora & Drago, 1994).

The canine cases here described shared haematological (anemia) and biochemical (high muscular enzymes at rest) abnormalities together with the unexpected presence of micrococci in blood smears (fig. 1, 2 and 5). These micrococci were similar to those previously observed in horses diagnosed with CFS (Tarello, 2000). No other typical blood canine parasite was detected .

Micrococci in the blood were not found in smears made after thiacetarsamide sodium therapy, suggesting an underlying chronic bacterial infection. The isolation of a vancomycin-resistant mannitol-fermenting Staphilococcus xilosus strain from a pustule (fig. 3 and 4) in association with CFS-related symptoms was similar to the association between coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. and chronic fatigue/chronic pain disorders in humans (Butt et al., 1998; Dunstan et al., 1999), and between pyoderma and CFS in horses with micrococci in the blood (Tarello, 2000).

In this study, an environmental aspect of interest is the living place of the subjects: a farm where edible mushrooms were artificially cultivated on beds of manure coming from intensive breedings of cows, pigs and poultry. The drinking water for the dogs was collected from a well near to the artificial lake in wich the cultivation waters were discharged every day. Manure used for such cultivation may be a source of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE).

The identification of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus xilosus strain from the drinking water suggested acquisition from an environmental source and also a relationship with the clinical picture, because the CFS-related symptoms and pyoderma recovered following therapy and a change in the water supply. An increased incidenc of pediatric CFS cases has been described in clusters of people drinking unpasteurized goat milk (Bell et al.,1991).

In my experience , the presence of such microrganisms is the only remarkable difference between fresh blood smears taken from healthy and chronically fatigued animals. This finding seem to confirm the report of a newly-identified human blood bacterium (HBB) which is claimed to be present in high number in the blood of persons who have CFS or Multiple Sclerosis (Lindner L. & McPhee K., 1999). These authors have no evidence that the bacterium can be completely eliminated using the standard FDA approved antibiotics and they affirm that under certain circumstances antibiotics can actually stimulate bacterial growth and make the patient worse. In the present study, the lack of responsiveness to previous standard therapeutic agents, suggested an antimicrobial-resistance of the underlying agents.

The therapeutic efficacy of arsenic on pyoderma is acknowledged in both human (Stone & Willis,

1968) and veterinary (Hutyra et al.,1949) medicine. Furthermore, The Merck Index (1976) lists

several arsenical veterinary preparations as tonics, useful against general debility and various

dermatological diseases. However, no relationship has ever been established with underlying

chronic bacterial infections or with the presence of micrococci in the blood. Recently, a 50% of

successful rehabilitation has been described in human patients with chronic fatigue syndrome

treated with a staphylococcus toxoid vaccine (Anderson et al., 1998).

In this report, high serum CK (>100 IU/L) and LDH (>300) at rest, were detected at first examination but not following therapy, when the symptoms had disappeared. The laboratory results and the symptoms observed (weakness, muscular pain, lameness) seem to indicate a possible systemic myopathy. Interestingly, myopathy with atrophy of both types of the fibre and severe mitochondrial abnormalities have been described in goats artificially raised in conditions of dietetical arsenic deficiency (Schmidt et al.,. 1984) .

The size and shape of mitochondria reveal abnormalities in up to 75% of CFS patients (Behan et al.,1991) and in dogs with episodic weakness associated with myopathy and high muscle enzyme activities (Breitschwerdt et al., 1992). High CK values have been already observed in a subset of CFS patients , particularly in those with seizure, ataxia and sudden onset of symptoms (Preedy et al., 1993). Human sufferers have shown also high GOT values (Komaroff, 1988) in 25% and relevant LDH activity in 0.3% (Bates et al., 1995) of cases.

At present time it is difficult to undestand the peculiar mechanism of action of thiacetarsamide sodium, an organic trivalent arsenical drug, in these CFS canine cases. Arsenic, which is known to selectively bind to thiol or -SS- groups of proteins (Cobo & Castineira,1997) in particular concentrations with iron in solution have showed to inhibit bacterial growth in mixed culture of thermophilic bacteria, with As(III) reported to inhibit bacteria to a greater degree than AS(V) (Breed et al., 1996). Arsenical have been used as medicines for thousands of years, in particular against bacterial infections, syphilis, tubercolosis and scrofulosis ( Kasten, 1996; The Merck Index, 1976) and have shown to have beneficial actions when fed in very small amount to laboratory animals (Anke, 1986). Experiments with different species have provided circumstancial evidence that arsenic is essential and that it may have a role in methionine metabolism (Uthus, 1994).

In summary, a multi-drug resistant cluster of canine chronic fatigue syndrome showed complete clinical and hematological remission 7 days after treatment with thiacetarsamide sodium, an organic trivalent arsenical given intravenously in low dosages (0.1/mlk/Kg/day) for 3 days.

Severe skin lesions were associated with CFS-related symptoms, presence of micrococci-like organisms in the blood, high muscle enzymes and the recovery of two vancomycin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus xilosus from drinking water and a lesion. Although serologic tests for CFS do not exist, it seems worthy to suggest that the presence of micrococci in the blood could be used as a diagnostic for this syndrome, because they apparently are the main hematological difference observed between healthy and chronically fatigued animals. The striking degree of activity of an arsenical drug in this cluster and in previous animal cases, seem to indicate a novel antimicrobial approach to CFS-like conditions in veterinary medicine.

Anderson M., Bagby J.R., Dyrehag L. & Gottfries C. (1998). Effects of staphylococcus toxoid vaccine on pain and fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome. European Journal of Pain, 2, 133-42.

Anke M. (1986). Arsenic. In Trace Elements in Human and Animal Nutrition. Mertz W. (ed.) Academic Press, pp.347-372. Orlando, FL.

Bates D.W., Buchwald D., Lee J., Kith P., Doolittle T., Rutherford C., Churchill W.H., Schur P.H., Wener M.& Wybenga D. (1995). Clinical laboratory test findings in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine, 155, 97-103.

Behan W.M.H., More I.A.R. & Behan P.O. (1991). Mitochondrial abnormalities in the post-viral fatigue syndrome. Acta Neuropathologica , 83, 61-5.

Bell K.M., Cookfair D., Bell D.S., Reese P., & Cooper L. (1991). Risk factors associated with chronic fatigue syndrome in a cluster of pediatric cases. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 13,(Suppl. 1), 32-8.

Bell D.S.(1994). The Doctorís Guide to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., U.S.A

Breed A.W., Glatz A., Hansfold G.S. & Harrison S.T.L. (1996). The effects of As(III) and As(V) on the batch bioleaching of a pyrite-arsenopyrite concentrate. Mineral Engineering, 12, 1235-52.

Breitschwerdt E.B., Kornegay J.N., Wheeler S.J., Stevens J.B. & Baty C.J. (1992). Episodic weakness associated with exertional lactic acidosis and myopathy in Old English Sheepdog littermates. JAVMA, 201, 731-6.

Butt H.L., Dunstan R.H., McGregor N.R., Roberts T.K., Zerbes M & Klineberg I.J. (1998). An association of membrane-damaging toxins from coagulase-negative staphylococci and chronic orofacial muscle pain. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 47, 577-584.

Cobo J.M. and Castineira M. (1997). Oxidative stress, mitochondrial respiration, and glycemic control: clues from chronic supplementation with Cr3+ or As3+ to male Wistar rats. Nutrition, 13, 965-70.

Dunstan R.H., McGregor N.R., Butt H.L. & Roberts T.K.(1999). Biochemical and microbiological anomalies in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: the development of laboratory based tests and the possible role of toxic chemicals. Journal of Nutritional & Environmental Medicine, 9, 97-108.

French G.L. (1998). Enterococci and vancomycin resistance. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 27, 75-83.

Fukuda K., Straus S.E., Hickie I., Sharpe M.C., Dobbins J.G. & Komaroff A.(1994). The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 121, 953-9.

Gambarotto K., Ploy M-C., Turlure P., GrÈlaud C., Martin C., Bordessoule D. & Denis F. (2000). Prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in fecal samples from hospitalized patients and nonhospitalized controls in a cattle-rearing area of France. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 38, 620-24.

Garvin K.L. Hinrichs S.H. & Urban J.A. (1999). Emerging antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Their treatment in total joint arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop., 369, 110-23.

Glass T. (1998). The human/animal interaction of Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome: a look at 127 patients and their 462 animals. Medical Professional with CFIDS (MPWC) News , 3, 2.

Hutyra F., Marek J. & Manninger R. (1949). Patologia speciale e terapia degli animali domestici. Pp. 645-646. Vallardi, Milano.

Ishitsuka K., Hanada S., Suzuki S.,Utsunomiya A., Chyuman Y., Takeuchi S. Takeshita T., Shimotakahara S., Uozumi K., Makino T., Arima T. (1998). Arsenic trioxide inhibits growth of human T-cell leukaemia virus type I infected T-cell lines more effectively than retinoic acids. British Journal of Haematology , 103, 721-8.

Johnson H. (1996) Oslerís Web. Inside the labyrinth of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Epidemic. Crown Publishers, Inc., New York.

Kasten F.H. (1996). Paul Ehrlich: Pathfinder in Cell Biology. 1. Chronicle of his life and accomplishments in Immunology, Cancer and Chemotherapy. Biotechnic & Histochemistry, 71, 2- 37.

Komaroff A.L. (1988). Chronic fatigue syndromes. Relationship to chronic viral infections. Journal of Virology Methods, 21, 3-10.

Koshiuka K., Elstner E., Williamson E., Said J.W., Tada Y. & Koeffler H.P.(2000). Novel therapeutic approach: organic arsenical melarsoprol alone or with all-trans-retinois acid markedly inhibit growth of human breast and prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. British Journal of Cancer , 82, 452-8.

Levine P.H. (1998). What we know about chronic fatigue syndrome and its relevance to the practicing physician. American Journal of Medicine, 105, 100-103.

Lew Y.S. , Brown S.L., Griffin R.J., Song C.W. & Kim J.H. (1999). Arsenic trioxide causes selective necrosis in solid murine tumors by vascular shutdown. Cancer Research, 59, 6033-7.

Lindner L. & Mc Phee K. (1999). Human blood bacterium. WIPO patent WO9924613A1, issued May 20, 1999.

McGregor N.R., Butt H.L., Dunstan R.H., Roberts T.K., Zerbes M. & Klineberg I.J. (1998). Toxic coagulase negative staphilococci are associated with changes in urinary organic and amino acid excretion in chronic facial muscle pain patients. The clinical and scientific basis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: from myth towards management. International Meeting for Clinicians and Scientists, Sydney, Australia 1998. The University of Newcastle and Combined CFS Consumer Groups.

N.I.A.I.D. (1996). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Information for physicians. Public Health Service. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1-16.

Preedy V.R., Smith D.G., Salisbury J.R. & Peters T.J. (1993). Biochemical and muscle studies in patients with acute onset post-viral fatigue syndrome. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 46, 722-6.

Rebora A., Drago F. (1994). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a novel disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Dermatology, 188, 3-5.

Ricketts S.W., Mowbray J.F., Yousef G.E. & Wood J. (1992) Equine Fatigue Syndrome. The Veterinary Record , July 18, 58-9.

Schmidt A.M., Anke B., Groppel B. & Kronemann H. (1984). Effects of As-deficiency on skeletal muscle, myocardium and liver. Experimental Pathology, 25, 195-7.

Soignet S.L., Maslak P., Zhu-Gang Wang, Jhanwar S., Calleja E., Dardashti L.J., Corso D., DeBlasio A., Gabrilobe J., Scheinberg D.A., Pandolfi P.P. & Warrel R.P. (1998). Complete remission after treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide. The New England Journal of Medicine, 339, 1341-48.

Soignet S.L., Tong W.P., Hirschfeld S. & Warrel R.P. (1999). Clinical Study of an organic arsenical, melarsoprol, in patients with advanced leukemia. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol., 44, 417-21.

Stone O.J. & Willis C.J. (1968). The effect of arsenic on pyodermas. Archives of Environmental Health, 16, 490-1.

Tarello W. (2000). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in horses: diagnosis and treatment of 4 cases. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 23(4),(revised December 1999, accepted for publication 28 March 2000, In press).

The Merck Index (1976). An Encyclopedia of Chemicals and Drugs. Ninth edition. Published by Merck & CO., Inc. Rahway, N.J., USA.

Thylefors J., Harbarth S. & Pittet D. (1998). Increasing bacteremia due to coagulase-negative staphylococci: fiction or reality ? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. , 19, 581-589.

Uthus E.O. (1994). Arsenic essentiality and factors affecting its importance. In Arsenic Exposure and Health. Chappel, W.R., Abernathy, CO. & Cothern C.R. (ed.), Science and Technology Letters, pp. 199-208, Northwood, UK.

Warrel R.P. Jr., Pandolfi P.P. & Gabrilove J. L. (1999). Process for producing arsenic trioxide formulations and methods for treating cancer using arsenic trioxide or melarsoprol. WIPO patent WO9924029A1, issued May 20, 1999.

CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME (C.F.S.) IN A FAMILY OF DOGSDIAGNOSIS AND

|

Walter Tarello, C.P. 42, 06061 Castiglione del Lago (PERUGIA) Italy. Email Author |