|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

|||||||

|

|

THERAPEUTIC GROUPS FOR CHILDREN: Spaces for words and thoughts By Dorella Scarponi - Section of Onco/Haematology, University of Bologna

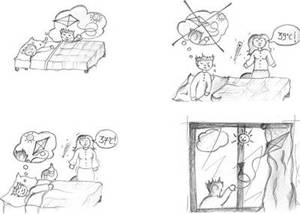

To the pediatric patient, almost always a minor, information about the illness comes in a selected way, after being discussed with the chief doctors, so that his/her psychic well-being is preserved, and in accordance with the equation: not knowing the truth equals knowing the kindest of truths. The child must let him/herself be treated, he/she must abide by the rules. Not by chance, after several experiences of hospitalizations, and more so during the phase of relapse of illness, the youngest children depict themselves as if they were completely transparent, already hairless, as if overrun by the events  When experiencing further suffering, the youngest children try to react bursting into rage crisis; they refuse to play, interrupt the normal vital flux that binds them to their siblings. Together with their parents, they make up funny names to call their disease, an imaginary compromise that becomes useless if, in time, it does not undergo a communicational revision. The anguish is related to being abandoned, being left free falling into unknown worlds, all alone or in the company of dead people seen only in photographs  In contrast, the adolescent holds back all his/her fear of dying and exasperates sophisticated defenses - rationalization, intellectualization, sublimation - around signals of deep psychological suffering. The idea prevails that pronouncing definitive words about the illness, such as a correct diagnosis, is equivalent to endowing it with realness, as though keeping silent about it authorizes the creation of areas of illusion and/or omnipotence.  The proposal to be part of groups (work, thought, play, therapy groups) led by a therapist, with the goal of creating opportunities for communication and confrontation around very deep issues, such as the choice of the therapy, the alliance before the cure, the fear and the pain has been accepted well by the patients. We are not just considering the repercussions that communication of the diagnosis has on the patient and his/her family, but we are also thinking of the never-ending work of redefinition, within the mind of every single little child, of the implicit communications he/she receives during the different phases of the illness, especially during the crisis times such as during the relapse of the illness, or haematopoietic stem cells transplantation, and the terminal phase. The intention, when taking care of children in a group, is that of increasing communication. By allowing the silenced emotions to reach a place, through a "sharing state" with the therapist and the peer group, each child’s willingness to hope can be cultivated, authentically, not only with regards to the possibility of healing but more generally to that of being cared for. THE PAIN THAT CAN BE TOLD The reckoning of an experience Therapeutic groups made up of small children indicate a great deal about their understanding abilities. While being psychologically supported on an individual basis during the first stages of the illness, once the consolidating therapy has begun, the patients are selected so that they can be moved to smaller groups. These groups take place once a week, last about one hour and are run in a Day Hospital room. Plunged into an environment where contacts with the pro carer are brief but the waiting time endless, groups follow one another. Group attendance is influenced by the fact the many patients originate from the Central-Southern Italy and by the possibility that other patients (affected by bone marrow aplasia) might be in need of hospitalization. The first semi-open group started out with 5 patients, lasted 12 meetings and ended with the discharge of the patients from the Day Hospital regime by Christmas holiday. The whole group has been affected all the time by the liveliness of one of the patients, a 10-year old boy who likes to act as a leader by telling his adventures outside of here. They all look at him mesmerized, even a young girl older than him, still on the chair. L., one of his peers, couldn’t stand being in contact with he group and left it after the first meeting. L. comes from a family where they do not speak about the illness and where the only tolerated outside intervention is that of the teacher. F. and I. are attentive and silent but they smile at the hero’s joke. As the group continues, they all take part more actively in the pictorial productions as well as in the exchange of verbal communication. Every time that one of them is taken out, for blood withdrawal or for a medical examination, those who stay try to guess the type of intervention. When the number of participants decreases to three or two members, communication becomes more intimate and feelings and pain are the subject. The time they remained in three, F., I., and C., almost peers, start to talk about painful practices. C. has to take a p.i. and has already taken a tranquilizer. He starts to speak slowly, but he wants to stay with us. He draws scary monsters and asks me to draw some others. He attacks them and scribbles them out with a pen

He tells us what he does to avoid too much pain: he screams so as not to hear it. I. concentrates, thinking of something else. F. on the other hand does not cry anymore. When, during the group, C.’s mother comes inside to call him, he asks if it is really his turn. The others continue working while I tell him that we will wait for him and we will save his place with his drawings. After the "trick", C.'s mother comes back inside, excusing herself, but C. must tell me something. Lying on the bed with his eyes half-closed, he tells me "This time around I haven't screamed!". It is the first time. I tell him he was very brave. I hint at the fact that, perhaps, he has been telling us so much and in such a clear way about how he screams when he hurts that he did not have anything to scream about during the puncture. "It must be so…now I’ll sleep a while". I tell the story of C. in the small group. They are calmed by the fact that everything went well. During the last session of this group, there are three of us. We know that we are going to say "Good-bye". In the last-but-one meeting F. had worn a very nice colored suit with tones of greens and the group had noticed it. On that occasion, I. had left a drawing unfinished because he thought it was not nice, F. had asked to complete it . Today, while F. is already sitting at the table, I. enters with his mother. I immediately notice that he has a new suit , not blue as usual, but green, forest green. His mother tells me that she had to buy him some clothes, yesterday afternoon. I tell him that today they look a little alike. He is happy, eventually he feels the same as someone else. Together with F. they start to draw. I. tells us what makes him angry, so as to continue the conversation left hanging the last time. F. amuses himself when he gets angry, anyway for both it seems to be a "speakable" feeling. The group lasts a little longer. When I bring it to a close, we are the last ones left in Day Hospital. We say "Good-bye" with a hug. I look at the tone of their skin, so different, and the same forest green color as the clothes.....  |

|